La Otra Cara de Mexico, in San Miguel de Allende, has one of the finest curated collection of masks in all of Mexico.

Putting on a mask to hide one’s face is universal and part of a folkway that stretches back as far as 40,000 years. Mexico has a rich tradition of masking and for more than 25 years Bill LeVasseur has been roaming all over Mexico collecting masks that became a museum in 2006 in San Miguel de Allende.

“La Otra Cara de Mexico” (The Other Face of Mexico) is more than a collection of masks on walls. This is a carefully curated museum, organized by categories, with detailed explanations that tell the story behind the types of masks and how they are used. History and culture buffs get a close look into this distinctive element of village celebrations while at the same time having a highly enjoyable learning experience.

To some, these masks might be frightening, but to others, they represent important aspects of culture and history.

Bill LaVasseur, owner and curator of La Otra Cara de Mexico (The Other Face of Mexico), is passionate about sharing his knowledge of masks and their place in the culture of Mexico.

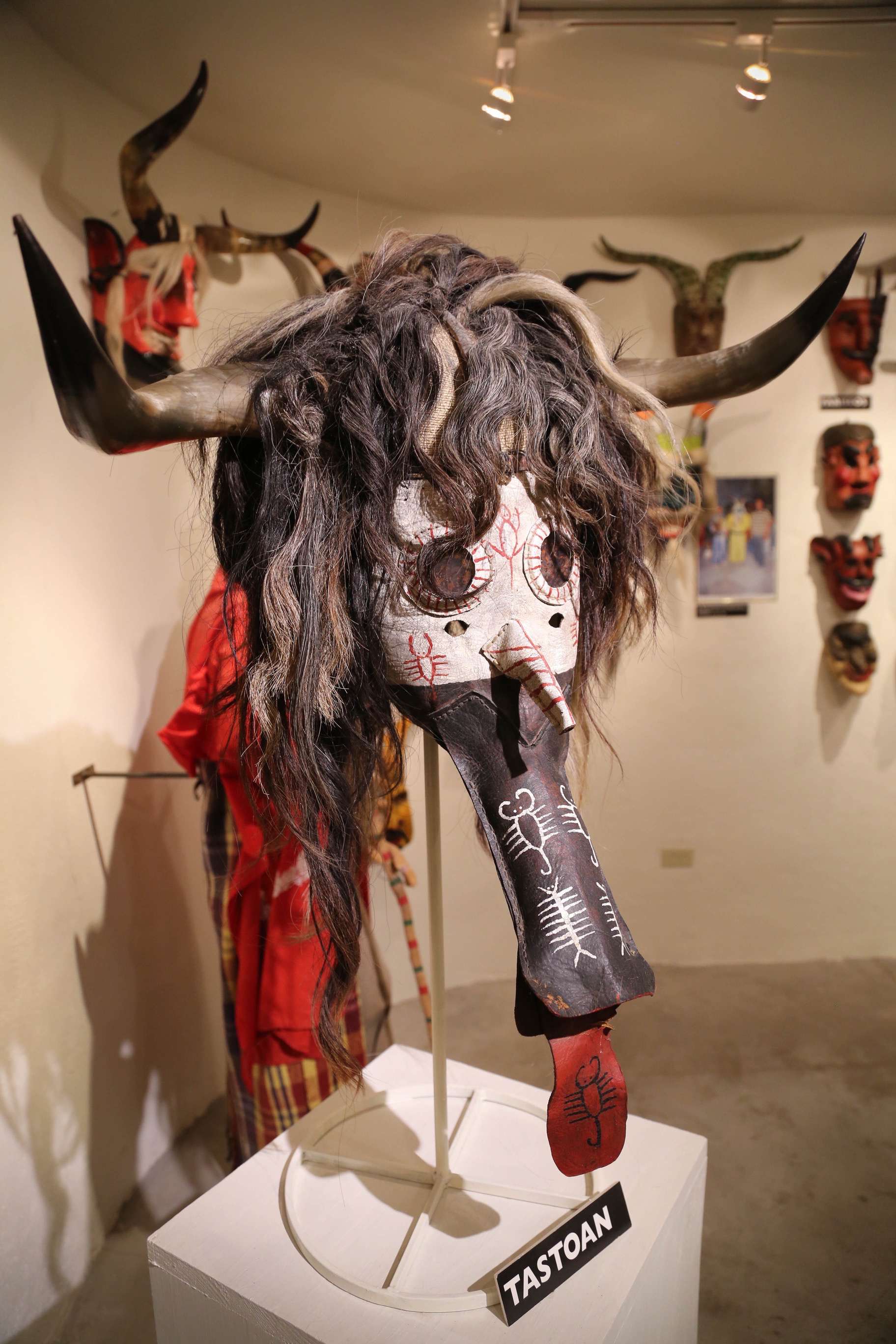

LaVasseur created a space to give visitors an appreciation of the history, purpose and meaning behind the masks in his collection. He explains that masking is a transformational event and experience, and masks fall into one of three categories, anthropomorphic, polymorphic, and zoomorphic. As one example, to put on a jaguar mask is to become the jaguar, while some masks are archetypal or are meant to be scary, like devils. In northern parts of Mexico religious-themed masks are more common, while that practice is found less so in southern parts of Mexico.

Bill LaVasseur has amassed and curated an incredible collection of ceremonial masks showcasing many aspects of Mexican culture.

Aside from the number of masks on display – more than 600 – the collection is special in that each mask has been used in a ceremony, giving it unmatched authenticity (as opposed to a mask purchased in a shop). LaVasseur spent decades attending festivals and ceremonies, coming to know people in villages and towns, and gaining their respect for his deep appreciation for their masks and what they mean.

This wall of “Moros” represent the Moors’ reenact struggles with the Cristianos, but the Moors come out the losers.

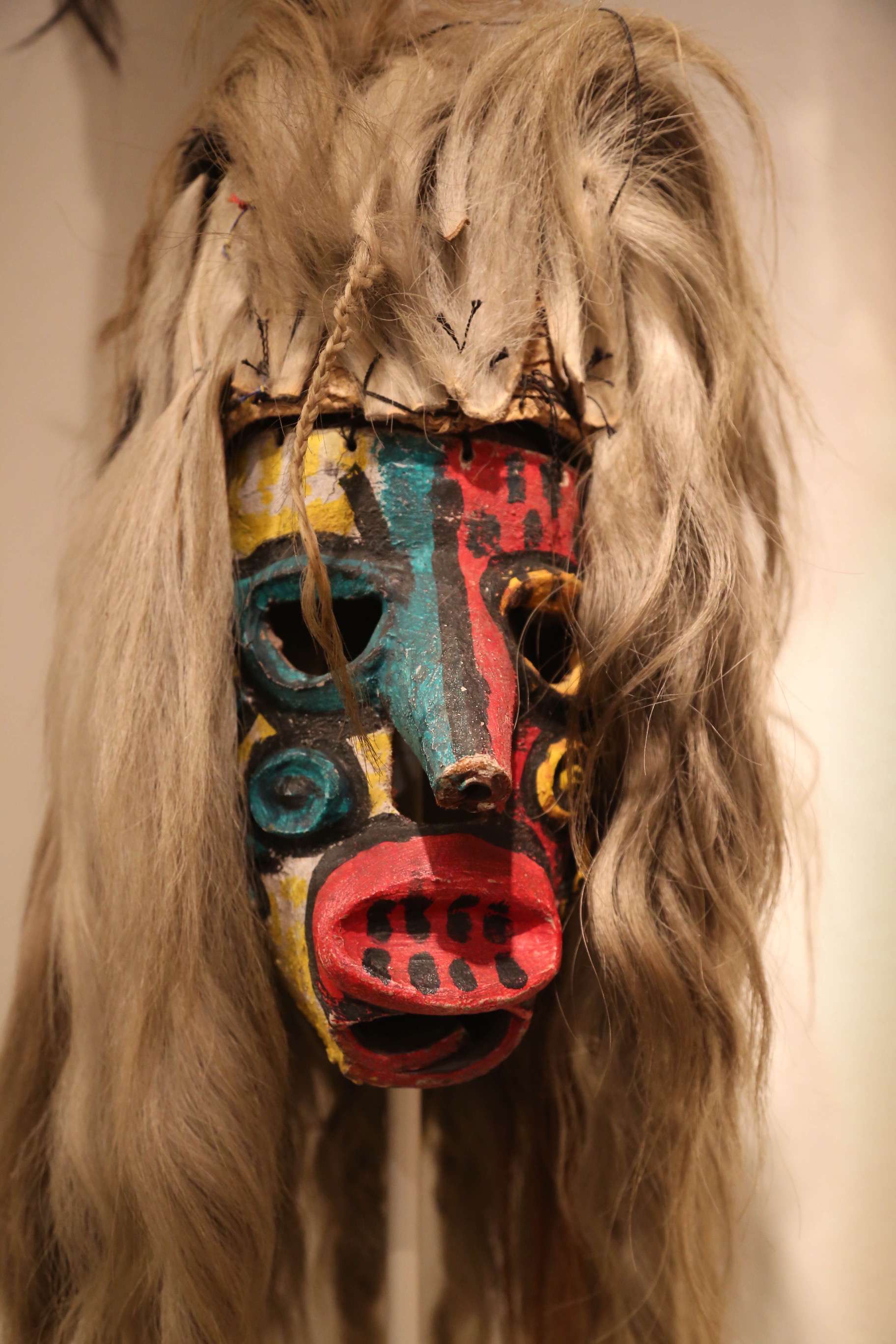

One mask in the collection is estimated to be nearly 200-years old, one has a moveable jaw and is likely at least a century old, and a great many show the wear and tear of having been used in ceremonies, and in some cases passed down from one generation to the next. Up to 90 percent are made of wood, some of leather or papier-mâché, and more recent examples might include plastic, fiberglass, sequins, or ribbons for decoration. The thinner the mask’s wood the easier it is to wear for long periods, but it is also vulnerable to breaking during carving.

The thinner the wood, the easier it is to wear for long periods. But a thin mask is more fragile and shows its wear, like this one.

Older masks are carved from a single piece of wood and these two show the skill of the maker, due to the thinness of the mask.

Some of the masks in the Museum are paired with the elaborate costumes that transform the wearer from head to toe and illustrate the character he becomes. A family might own a particular mask, while some are the collective property of the town or village.

Using materials, like the sequins in this costume creates a vibrant look not possible a century ago.

Modern materials, like ribbons, manufactured beads and plastics shows the evolving nature of mask making.

Acquiring a mask for his collection is no easy feat. LaVasseur spends a great deal of time cultivating the trust of the owners. He respectfully asks the town council for permission to attend a ceremony or festival, and in the acquisition phase he pays careful attention as to how an owner refers to a mask, and if LaVasseur senses a mask is not for sale, he never presses the issue. If a mask belongs to the community he will not purchase it.

Mask making is a craft carried out almost entirely by men, but as modern times have overtaken old traditions (young men moved on to work in cities or the United States), women have begun to take up some of the work of mask production and repair.

LaVasseur has a laid-back demeanor but his passion for his collection clearly shows. He takes care to explain the history of masking, and he wants visitors to appreciate the cultural significance of masks in Mexico. The museum is carefully laid out with detailed explanations that reflect the cultural context and the facility is on par with any high-quality museum.

While only open by appointment, the museum has become a popular learning venue for San Miguel de Allende’s school children. La Vasseur estimates about 30 students per week tour the museum. Nor is his passion a venture designed to make money as he donates the modest entry fee (for adult visitors) to a local charity.

Information signs in both Spanish and English provide museum goers with background on the type of mask and its meaning.

Visit “La Otra Cara de Mexico,” and you come away with the understanding that masks might well conceal, but they are also a way to transform, and along the way you gain a deeper appreciation for the rich cultural heritage of masks in Mexico.