When these pieces of glass were handmade by skilled craftsmen in Zadar during the Roman Empire, they were status symbols for their owners. The stain on the large piece are remnants of earth where the piece rested for many centuries.

Several thousand years ago glass products were generally drab and uniform in color — somewhat clear, with hints of blue or tints of green. Nowadays glass can be produced in a wide variety of vibrant colors.

Glass is as old as Earth, back when the planet was no more than a fury of thermo-electro-chemical clashes as the solar system took form and Mother Nature’s elements grabbed their chairs and tucked into their seats at the periodic table.

These bottles, recovered around Zadar, in the northern region of Dalmatia in Croatia, are important for several reasons. They are intact, they demonstrate a sophistication of production, and the imperfections of shape and angle show the challenges glass makers faced when making their products.

The world’s first glass was untouched by the hand of man, naturally produced, either from the tectonic maelstrom of volcanic activity that resulted in obsidian, or from the heavens when a billion volts of lightning exploded and flash-melted silica-rich sand to leave bizarre multifurcated sculptures.

One of the benefits to using glass containers is you can immediately see what’s inside. Herbs, spices, and foods could be easily stored and quickly selected as needed.

A jar without a lid is useless if you want to preserve freshness and flavor, and this collection of lids were once mated to their own jar.

As the chemistry, thermodynamics, and manufacturing process of glassmaking became understood, humans began to see the material in an entirely different light. The Zadar Glass Museum, the only one of its kind in Croatia, offers a comprehensive look at glass and glassmaking that harkens back to the Roman era. As an added benefit, on-site glassmakers create fascinating pieces while you watch.

Glass making has always been a mixture of craft and art. This highly talented artisan carefully heats the glass to bring it up to a temperature so the molecular structure softens and she can create a piece of wearable art, like the ring on her right hand or her necklace. The leftover bits and pieces on her work table are the glass maker’s equivalent of wood chips or stone flecks that would be produced by artists who work in other mediums.

Time, patience, and practice are some of the best teachers for glass makers so they know just how fast to heat a piece, and how hot it needs to be in order to best work the material.

Eye protection is essential for close-work glass makers — shattered glass could be blinding. The tinted lenses are both protective and the color of the lenses helps her see “through” the bright flame in order to produce her best work.

The constituent components of glass are simple. Sand, with a high silica (quartz) content is heated to more than 3,100 degrees Fahrenheit and the molecules combine into a state that can be worked. But getting temperatures that hot was difficult as far back as 3,500 B.C., so the first human made glass was generally small ornamental pieces. Mesopotamia is considered the first place where humans made glass, but techniques quickly spread to other regions of the world. When glassmakers learned to create much higher temperatures – using forced air, specially-designed heating ovens, and coal, glassmaking evolved to include containers, vases, art pieces, and windows. Early windows were referred to as crown glass.

A bowl this colorful and bright is possible because of the advances made in chemistry that would give this piece it’s dazzle and pop.

An observer might be forgiven if they thought these were wax candles, but they are glass rods imbued with various chemicals and compounds that will lend bright colors to clear glass. A pair of discarded vases sit on top.

People of today might take this bowl for granted, along with the component decorative pieces that went into it. The small pieces, lower right, look just like tasty hard candy. Had this bowl been around in the first or second century A.D., it would have surely been highly prized.

Various components can be added to give glass different colors and properties and the artistry of stained-glass windows was one result. Popularized by churches, the wealthy, and royalty, stained glass windows served a dual purpose. They let in light to make the inside space more welcoming, and windows became a canvas to tell important stories (often from the Bible; important when literacy was low). For centuries the high cost of manufactured glass made it a luxury item far beyond the reach of anyone but the wealthy.

These pieces, recovered by archeologists from sites in the Zadar area, show how early glass makers were able to make small pieces that could be turned into jewelry and other decorative pieces. The molten glass was laid upon the rod and once it cooled it slipped off the rod.

To the untrained eye, this would look like a simple glass bead necklace — which it is. At the same time this is an outstanding example of how early glass makers created colored glass that was made into beads, and in this case, strung into a necklace. The owner was surely the wife or consort or wealthy man.

Over time glass makers learned to add other materials to create properties such as improved clarity, greater strength, the ability to withstand extremely high temperatures, colors and tints. As examples, tempered glass can endure shocks and pressures that would smash an old glass pane. Borosilicate glass, commonly referred to as Pyrex, allows it to withstand extreme temperatures and shocks, important in a field like chemistry. Photochromic glass used in eyeglass lenses darken with sunlight and then return to a clear state when taken indoors. Adding lead to glass creates crystal, making the glass both very clear and heavier than other glass. And of course, the field of astronomy would be nowhere without ultra-clear glass.

The Zadar Glass Museum is highly respected for several reasons. Among them is the amount of glass on display, the quality of the pieces in the collection, and the variety. These small containers likely held perfumes, scents, or essences that would have been costly.

For centuries Zadar was an important outpost to the Roman Empire. The city and region thrived and glass making was an important part of Zadar’s commerce and trade. These small pieces recovered by archeologists show both the talent of the glass makers, as well as the staining of the earth as the pieces lay buried for centuries.

What is notable about the pieces in this photo are they are all standing on their bottoms, indicating a level of care and sophistication in their manufacture.

The Zadar Glass Museum is housed in a reconstructed villa and the venue includes a significant number of pieces that harken from the Roman Empire era. Zadar, like other locations along the Croatian coast, was an important outpost for the Romans.

The display rooms of the museum showcase an impressive collection of glass in all sorts of shapes and sizes.

The museum has been carefully curated and laid out to give visitors ample room to appreciate glass from the age of the Roman Empire.

This glass case of glassware allows visitors to get an up-close look at some of the many pieces that are a part of the Zadar Glass Museum.

Glassmaking, until around the first century A.D., was a time-consuming process that resulted in small pieces such as beads, or heavy, thick-walled containers. But around the First Century A.D., glassmakers refined techniques such as glass blowing, which allowed products to be made more quickly, with thinner walls, and consistent sizes and volumes. From there, the manufacture of glass products took off and glass became a much more commonly used product.

Glassblowing marked a significant advancement thanks to the development of the blowpipe — a long, hollow rod able to withstand the extreme heat of glass in its fluid state. Glass makers would gather molten glass at one end and very gently blow into the other end. Molds would give the containers a uniform size and shape.

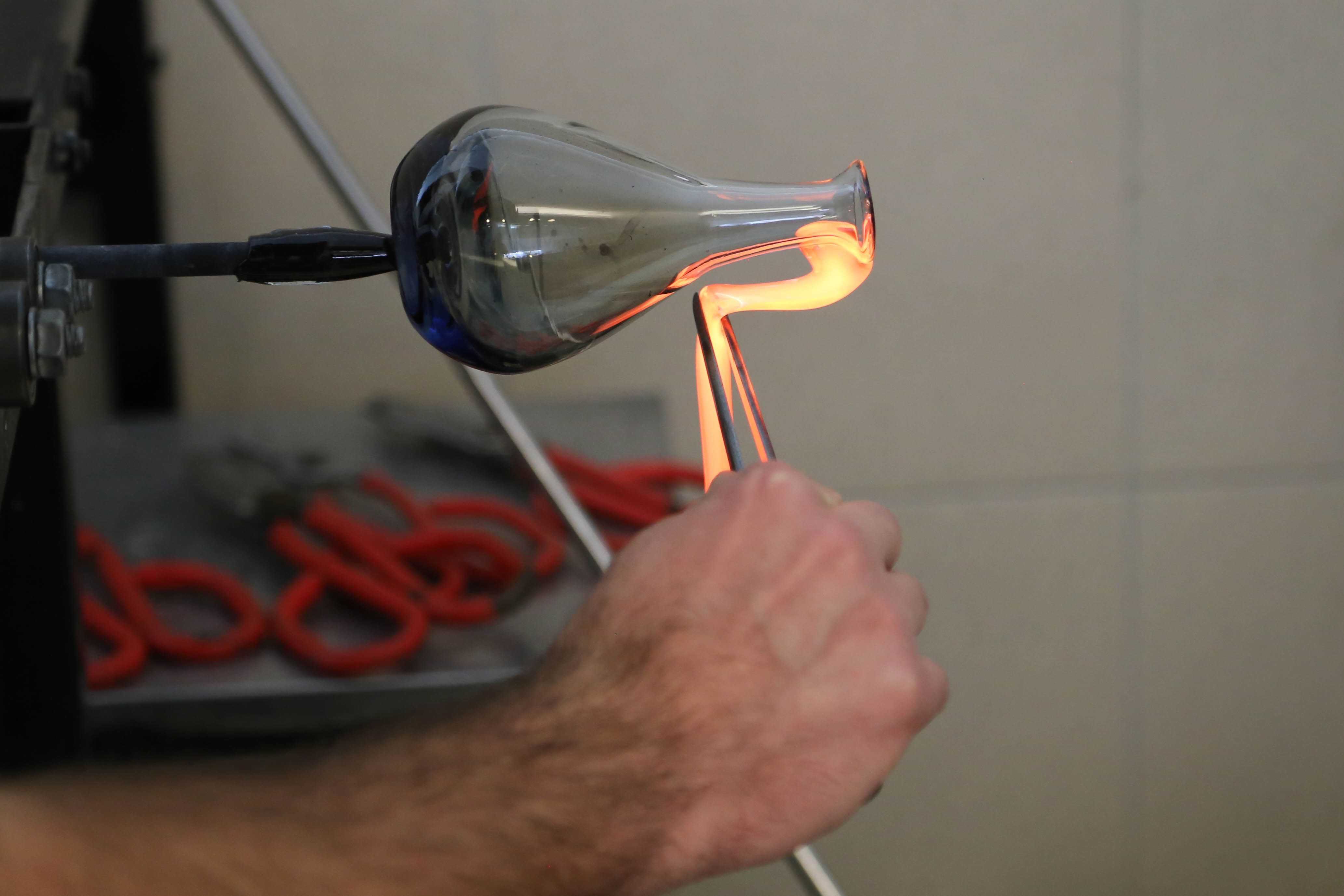

Glass is a solid that is heated to a near-liquid state that ends up becoming a solid again. Knowing how to work the glass is a technical skill and understanding how to make the piece beautiful is an artistic skill.

As the piece is being created, it must be returned to the oven from time to time, to keep it hot enough for the maker to work his magic.

The Zadar Glass Museum is not only a gorgeous building, the extensive museum collection is well presented. The extent of the collection makes it clear glass was an important part of Roman-era life (Romans occupied the area from about 49 B.C. to about 479 A.D.), and that its use expanded from bead jewelry to everyday use. Containers, glassware, bottles, mosaic tiles, and everyday items were produced as the knowledge of glassmaking expanded.

The artist rests the blow pipe on his bench and continually moves it back and forth, to maintain a round and even shape. He works the glass, including adding a flat surface to the bottom so it will rest on a table or shelf.

Now satisfied with the size and shape of the container, it’s time to separate it from the blowpipe. A file is used to score a line which will become the top of the container. Using a holding rod, a small dab of molten glass will be attached to the bottom and the top is snapped off from the blowpipe. The top will be heated again to melt down any sharp edges at the neck.

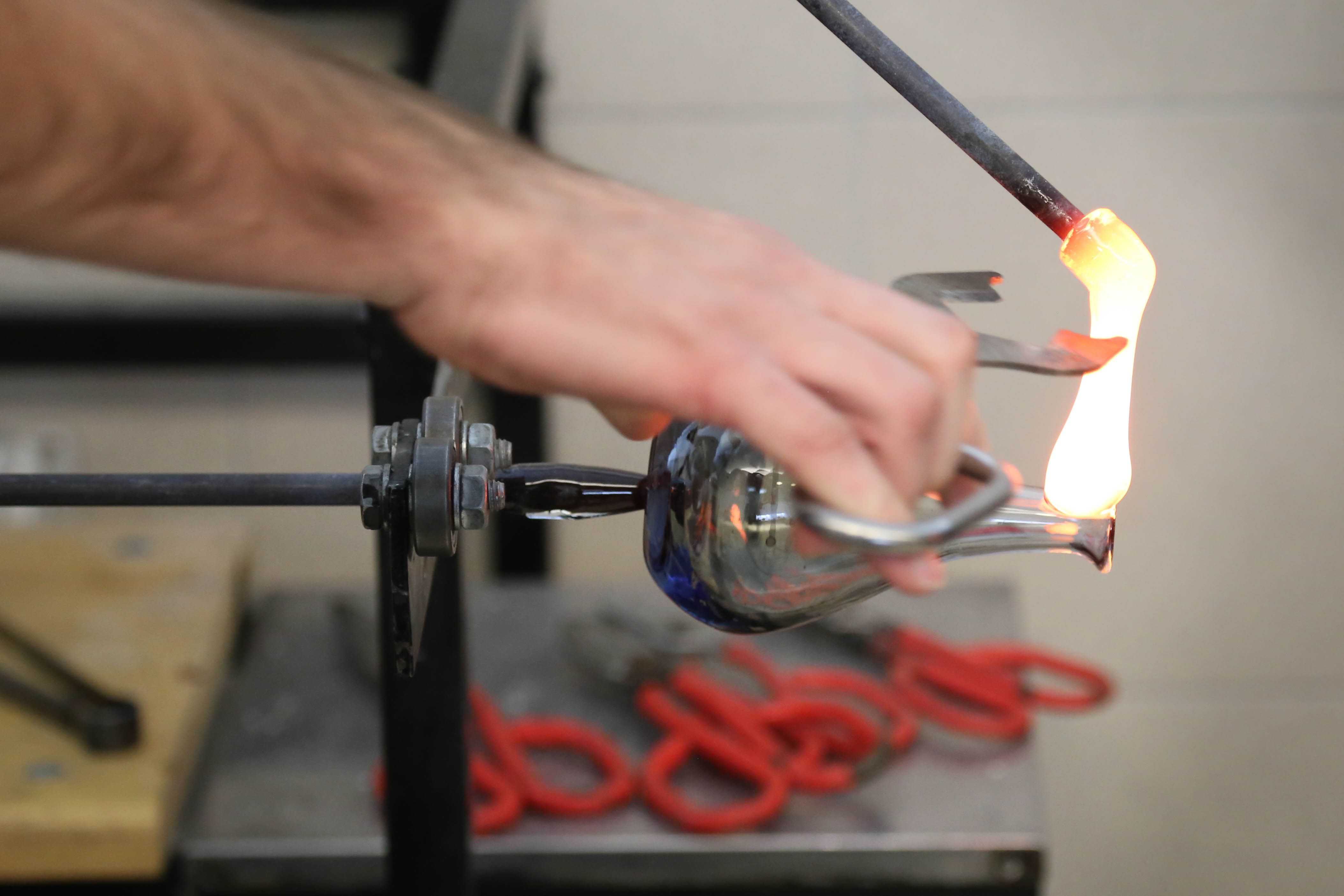

One of the final steps is to make a handle. A dollop of molten glass is attached and stretched out.

To complete the handle, the glass artist rotates the vase with the handle hanging straight down, attach it to another point on the neck, finishing the piece.

An added benefit at the museum is that throughout the day glass artists and glass blowers give demonstrations in two different parts of the museum. Whimsical pieces of jewelry and wearable art is made by highly skilled artisans, and a glass blowing workshop creates larger, more utilitarian pieces such as handblown works as visitors look on. Items made at the museum are available for purchase in the gift shop.

The fire and furious temperatures of glass making create havoc at the molecular level. Annealing is an essential part of the finishing process whereby the glass is heated over a period of time that allows the molecular structure of the glass to settle and finalize the atoms so they are aligned without stress.

Even though it is chipped, this cup shows a high degree of workmanship based on the thinness of the side.

Today, glass is a product that most people around the world come into contact with in their daily life. It has become so commonplace that many people take it for granted. From windows that let light shine into our homes, lenses that help us see more sharply, windshields that keep out the elements while we drive, and the labware used by chemists and scientists as they search for answers to create medicines and cure diseases, glass is an integral part of our lives.

Evidence would suggest these small pieces were made after the first century A.D. using a mold in order to obtain the delicate textures.

This small piece of whimsy sat on a shelf in the glass blower’s workshop and showcases the skill and artistry that a talented glass maker possesses.

But when viewed at the Zadar Glass Museum, one steps back in time; when glass was a wonderous material that helped civilizations advance and now make the world an easier place to live.

Amphora is the shape of containers used by the ancient Greeks and Romans to store and transport a variety of foods, grains, and liquids. To find an intact specimen of this size attests to the quality of the glass making in ancient Zadar and the talent of the glass makers.

This piece could only have been made using a mold, given the well-defined shape and texture of the fish, meaning that it was made sometime after the first century A.D., when the blowpipe and molds were used to make glass containers.

A jar of this size with a lid would be as prized a piece in the home of a Roman elite, just as it is an important piece in the collection of the Zadar Glass Museum.

This mural on one of the walls at the museum shows what the life of a glass blowing team might have been like in Zadar during the era of the Roman Empire. The large oven, with just a few ports to heat the raw materials would have been constantly stoked to maintain the high temperatures needed to turn sand into a molten material.

For more information about glass and the Zadar Glass Museum, click over to these websites:

www.zadar.travel/city-guide/museum-of-ancient-glass

wikipedia.org/History_of_glass

vetropack.com/history-of-glass

www.cmog.org/origins-glassmaking

www.sciencealert.com/physics-of-glass

math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/Glass