Prior to and during World War II the synagogue was bombed, taken over by German Nazis, and would fall into disrepair before a major restoration that began in the late 1980s. The building is a combination of design styles including Moorish, Gothic, Byzantine, and Romantic.

When it was originally built in the late 1850s there were many more practicing Jews in Budapest and throughout Hungary than today. Now visitors of the world can sit and listen to the story of the temple in many languages. The woman, right, arm raised, is discussing the synagogue in Italian.

Hungary has a long – and sometimes fraught – relationship with Jews. Living in the Carpathian Valley centuries before Magyars formed a nation, Jews have been an important part of Hungarian culture, arts, science, business, and politics. The Dohańy Street Synagogue in Budapest is the largest synagogue in Europe (second-largest in the world) and the temple and museum tell the story of Judaism in Hungary.

The ark, where the Torah and Jewish Law are illuminated and bathed in the glow of an Eternal Light, is housed at the back of the altar

A closer look at The Holy Ark shows the beautiful design and great care of craftsmanship. The raised table facing the Holy Ark is called a bimah where passages from scripture are read and the service is conducted. A docent, standing, explains to a group of students the many significant facts about the synagogue.

Budapest was originally two cities, Buda and Pest, split by the Danube River and further divided into districts (there are currently 23). A core part of District VII on the Pest side is where the city’s Jewish population congregated. Residential property on Dohańy Street, owned by the Herzl family, became the site of the synagogue. A son, Theodor Herzl, would go on to be mentioned in the Israeli Constitution as the father of modern political Zionism.

The winding staircase of the pulpit enables the rabbi another vantage point to deliver a sermon to the congregation As a temple still in use, men and boys are required to wear head coverings. Yarmulkes are available for visitors.

Just before entering the main area of the temple, a woman pauses to inspect the names that have been memorialized.

Construction of the synagogue began in 1854 and was completed in 1859. Designed by a Viennese architect Ludwig Förster, the building is a blend of styles – Moorish, Byzantine, Gothic, and Romantic. Förster was not a Jew, but he designed a number of synagogues. At nearly 250 feet long and 90 feet wide, the temple can hold almost 3,000 worshippers. In 1859 Hungarian composer Franz Liszt and French composer Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns played the synagogue’s 5,000-piece pipe organ at the temple’s consecration on September 6. It was a proud time for Budapest and the temple’s faithful.

Winters in Budapest can be very cold and the main temple, pictured, is not heated, so a smaller sanctuary called Hero’s Temple, which can hold around 250 worshippers, is used for services on weekdays and during the winter months.

An exterior view shows the competing styles of architecture and locations of some of the stained glass window elements of the temple.

Prior to World War I approximately 5 percent of the population of Hungary was Jewish and in Budapest about 23 percent of the population called themselves Jews. (In 1910 Hungary had a population of more than 18 million people.) But rising anti-Semitism in Hungary at the end of World War I marked a dark turning point.

The size and scope of the Dohány Street Synagogue is evidence of the once-thriving and activity Jewish community in Budapest. This well-worn alcove would have been filled with worshippers as in this community of faith. A portion of Imre Varga’s “Tree of Life” can be seen through the archway, in the memorial park.

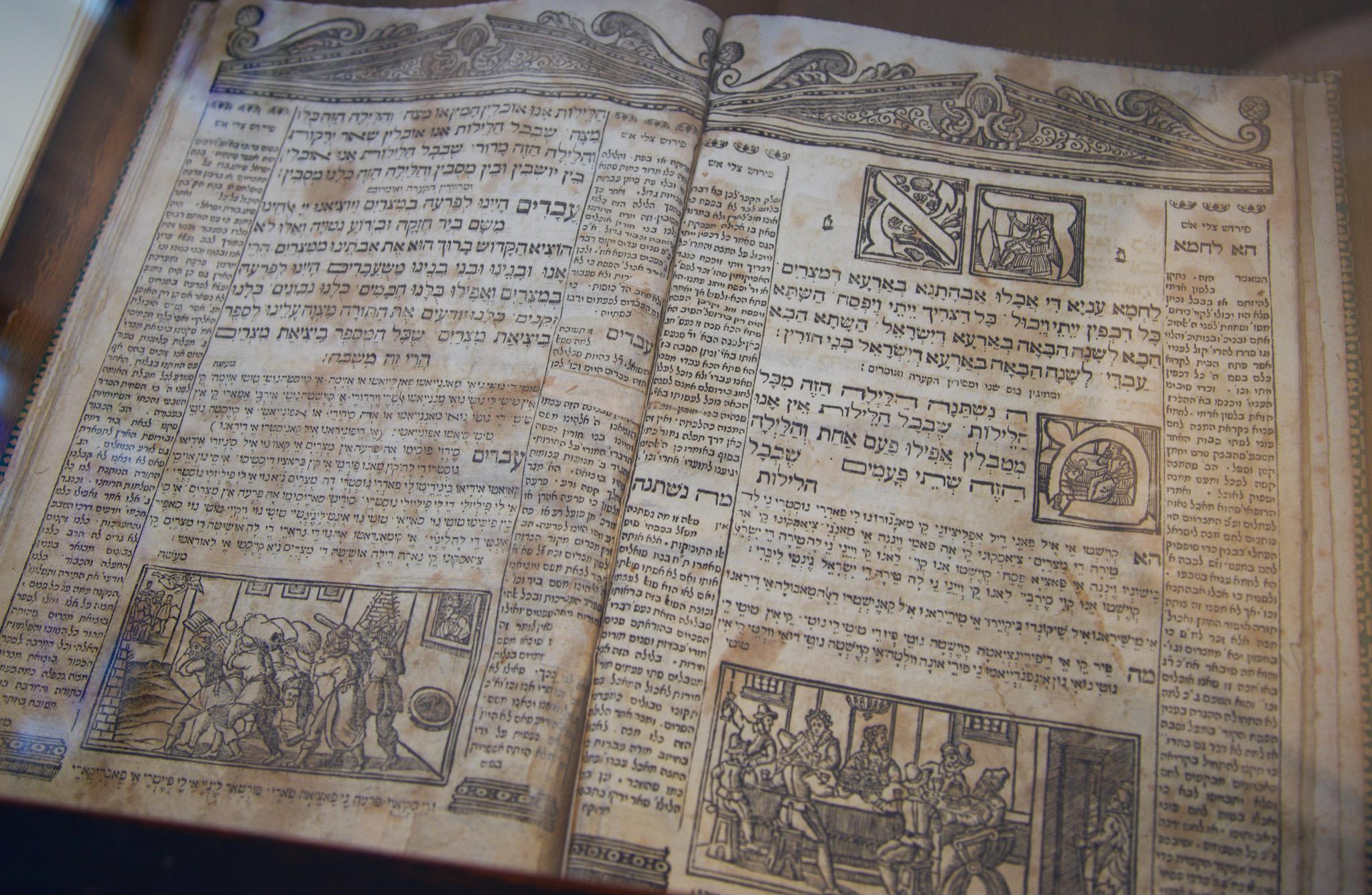

The display of religious texts, artifacts, and elements enables visitors, many of whom are not very knowledgeable about Judaism, to see and learn more about one of the world’s enduring religions.

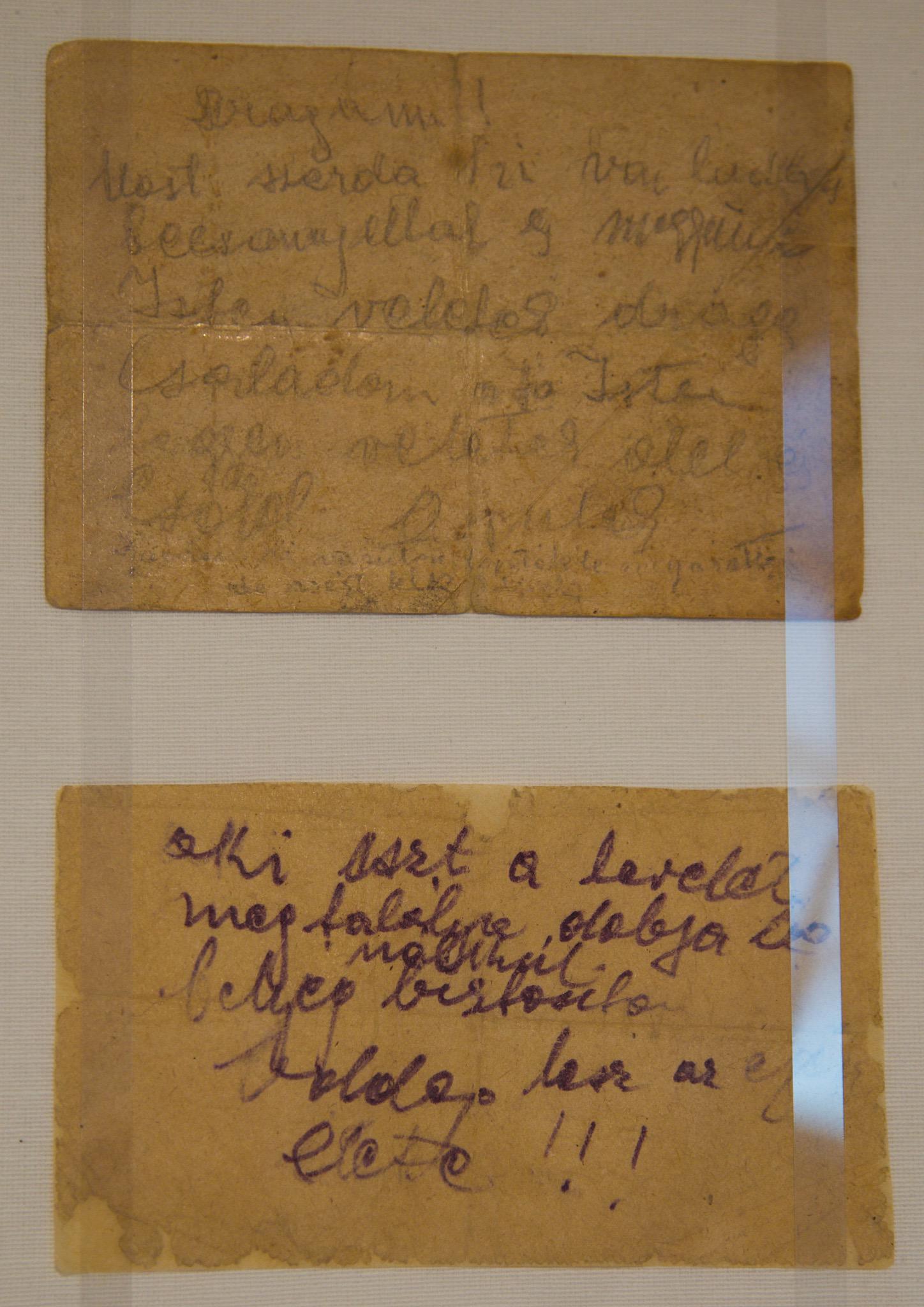

These handwritten notes are evidence of the determination people show when they try to reach out to those from whom they had been separated. The top one was tossed from a moving train car, later found and routed to the recipient who learned that someone they loved was still alive — at the time the note was written.

The losers in World War I – Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Ottoman Empire – were forced to sign treaties filled with crushing penalties and brutal consequences. Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles, the Austro-Hungarian Empire put their signatures to the Treaty of Trianon, and the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sévres. As examples, each of the losers lost huge parts of their territory and millions in population. These were not treaties of peace, but rather punishment, and they sowed many of the seeds that lead to World War II.

A pair of gates designed with matching six pointed Stars of David marks a boundary point at the Dohány Street Synagogue.

The rich archival collection in the on-site museum affords visitors an extensive look at the wealth of material that has been part of the Jewish community in Budapest and Hungary.

Hungary (like Germany), had its own fascist party, the Iron Cross Party, and in early February of 1939 Iron Cross thugs bombed the synagogue. It was one of many indignities and assaults that befell the temple before and during World War II. The German Nazi army used the synagogue as a radio broadcast center and a horse stable during part of the war. (The Arrow Cross Party committed their own atrocities upon Hungarian Jews as part of the horrors of World War II.)

Iconography like these religious artifacts, many of them silver, have been collected and placed on display at the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives.

This large, ornate, and artfully designed menorah is accented by lighting that gives one pause to reflect on the meaning of faith.

The end of World War II brought in the smothering hand of Communism, and the synagogue, like Budapest, and all of Hungary, suffered terribly. The temple desperately needed repair and restoration. But it was not until the Soviet Union fell apart in the late 1980s and Hungary turned toward democracy, that a climate of hope created an opportunity to return the Dohány Synagogue to its former stature. The three-year renovation cost $25 million and was funded by $5 million from the United States, substantial donations by Hungarian-Americans such as cosmetics entrepreneur Estee Lauder and acting legend Tony Curtis, and other generous donors.

The extensive 1990’s restoration of the synagogue included the beautiful stained glass windows that tell stories of the Jewish faith and bathe the interior in soothing light.

Stained glass windows became popular as a way to visually tell stories of faith, even for those who could not read, and to bestow a grandeur to the importance of Judaism.

The restored synagogue, related structures, accumulation of relics, artifacts, and records tell a marvelous story of faith and perseverance. Inside the temple, colorful frescoes, lighting, and stained-glass windows have been brought back to their earlier grandeur. Included within the complex is the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives that holds religious relics, a Holocaust Room, and other memorable objects of the Hungarian Jewish community. Hero’s Temple, with room for approximately 250 worshippers, is the place for weekday and winter religious services, and it also serves as the memorial site for Jews who lost their lives during World War I.

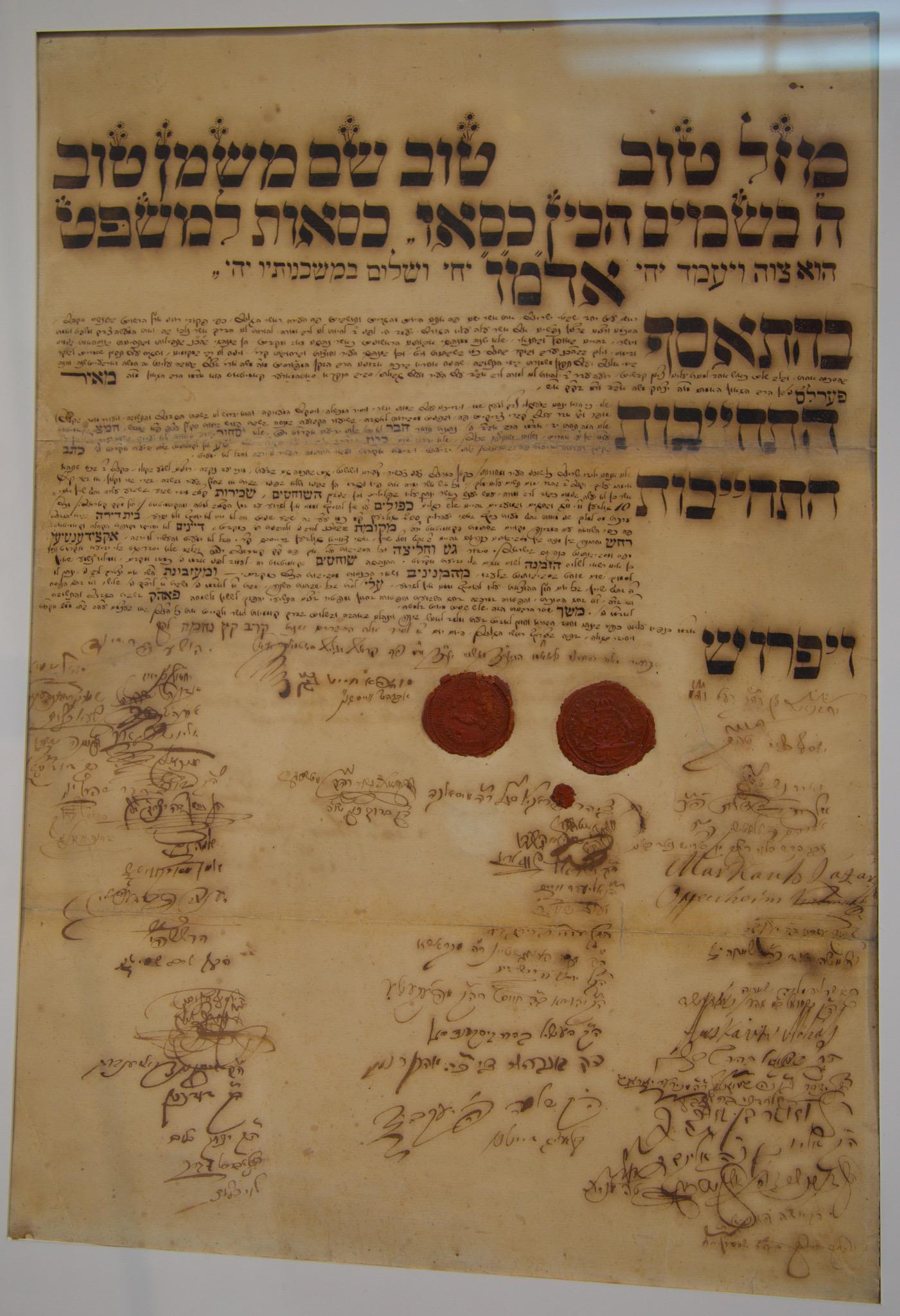

A great deal of effort was taken to collect and house the important artifacts of Judaism in Budapest and Hungary, like this legal document with a plethora of signatures and wax seals.

This large stained glass mural is a focal point on the grounds of the temple, serving as an anchor to the “Tree of Life” at the far end.

The Dohány Synagogue is unique among the world’s Jewish temples in that there is a cemetery on the temple grounds. Talmudic law and tradition say Jews are to be buried outside the city limits. But German Nazis and Hungarian Arrow Cross goons tortured and murdered thousands of Jews on the grounds of Dohány Synagogue. In 1944 nearly 70,000 Jews were squeezed into Budapest’s Jewish ghetto, and of that number, 8,000 to 10,000 perished, and 2,000 were buried in a makeshift cemetery on the grounds. To honor the dead and remember the atrocity, Hungarian sculptor and artist Imre Varga created a dramatic stainless steel weeping willow with the names and tattoo numbers of those murdered at the site inscribed on the leaves.

The “Tree of Life,” part of the Raoul Wallenberg Holocaust Memorial Park, was created by Hungarian sculptor Imre Varga. It has the name of each of the 2,000 Jews buried on the synagogue grounds, along with the tattoo numbers inked onto the victims’ arms by their fascist captors.

Upon closer inspection, each leaf has a name and corresponding number, of the 2,000 Jews buried at the cemetery. It serves as a vivid reminder of the brutality that took place in the nearby ghetto .

“Tree of Life” was designed with seven major branches, as a connection to the menorah, an important symbol of Jewish faith.

As many as 600,000 Hungarian Jews are part of the death toll of the Holocaust. And their memory is kept fresh as part of the Raoul Wallenberg Holocaust Memorial Park. Wallenberg, a Swedish architect, diplomat, and businessman went to extraordinary lengths during World War II to save many tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust. In addition to the weeping willow that is part of the memorial park, the story is told of the notable humanitarian efforts by Europeans, Catholics, and other brave people of conscience whose escamotage saved the lives of thousands more by issuing phony documents, travel papers, and concocted identities.

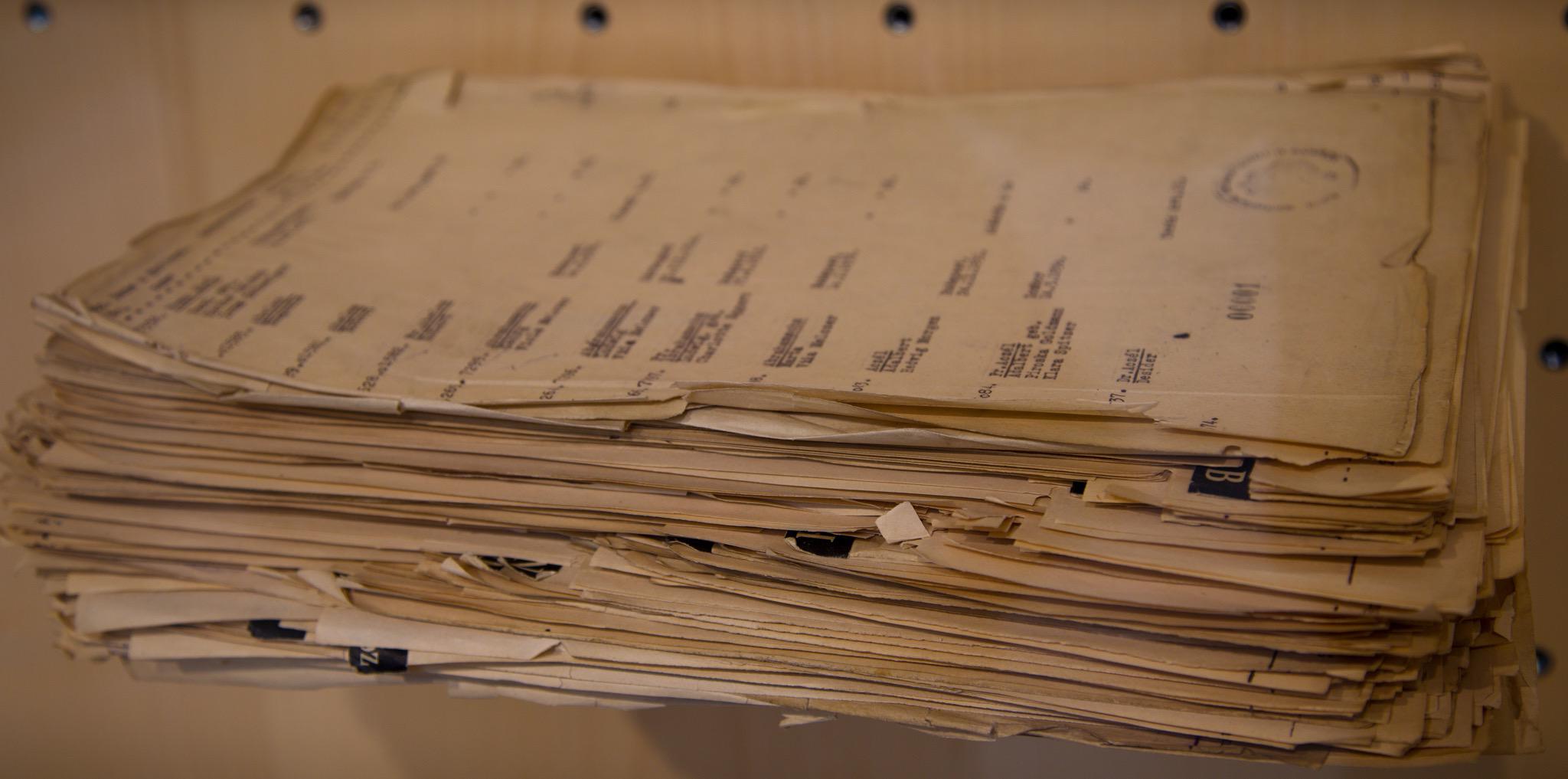

The stacks of papers with neat and ordered rows of data are the clerical records that now serve as a gruesome reminder of the administrative tally that was taken so fascists could keep track of those they were intent on exterminating.

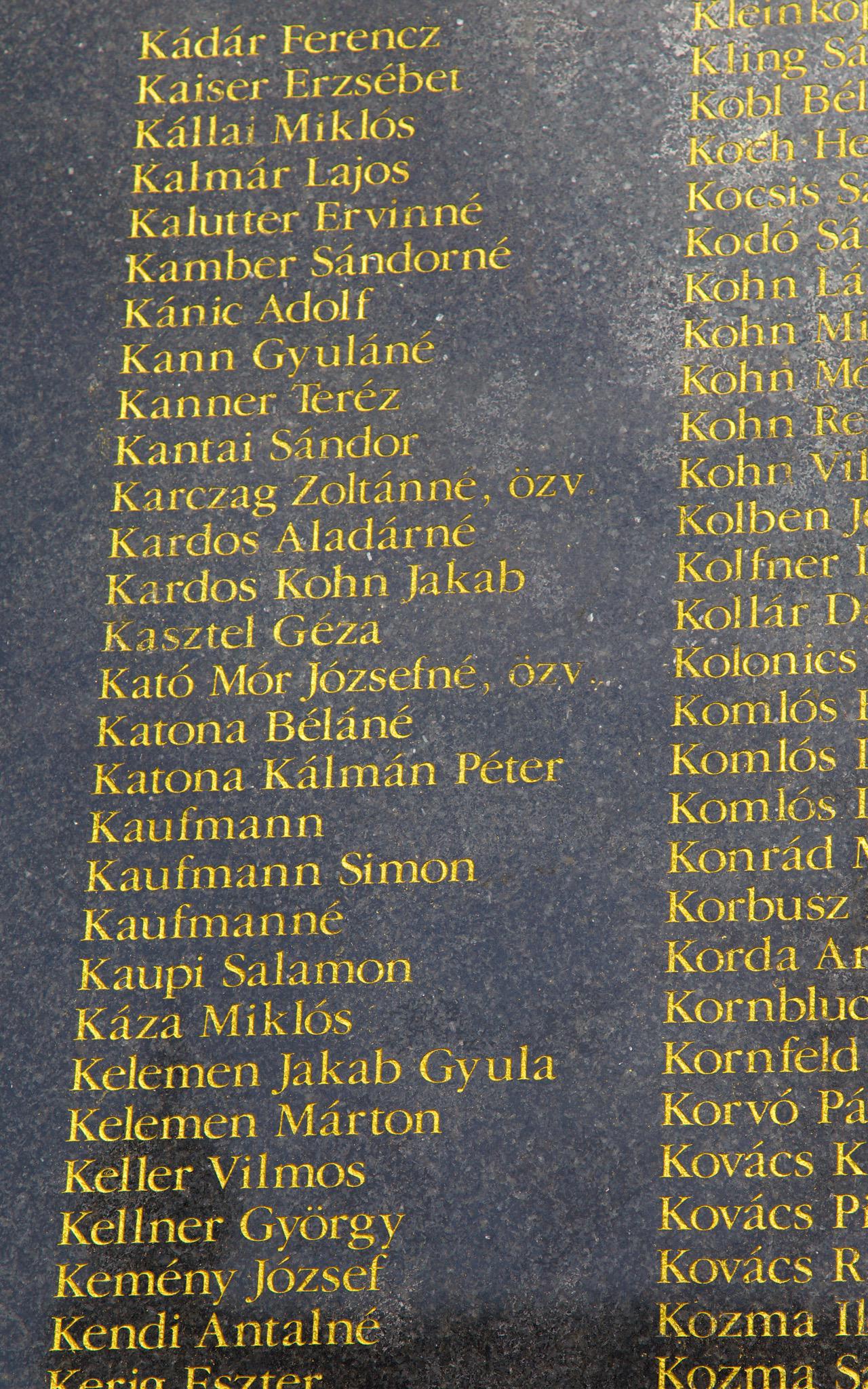

Left column, the 12th and 13th names on this list are the same last name as the author. Seeing those two names added a sobering personal moment of reflection.

Currently less than 0.2 percent of the 9.8 million Hungarians claim Jewish faith. The current Hungarian Constitution proclaims itself a “Christian nation” and the dominant political party, Fidesz, is a right-wing ultra-nationalist movement that uses a heavy hand to promote an “illiberal democracy.”

This courtyard displays markers of those buried on the temple grounds, lending a painful solemnity to an otherwise calm spot.

The restoration of the grounds of the Dohány Street Synagogue is an inviting space to visitors, while noting the importance of faith and reminders of what occurred here.

The struggle of Judaism in Hungary continues, but as is the strength of faith, the Dohány Synagogue in Budapest will continue to serve as a beacon of hope and source of pride for the Jewish faithful in Hungary and around the world.

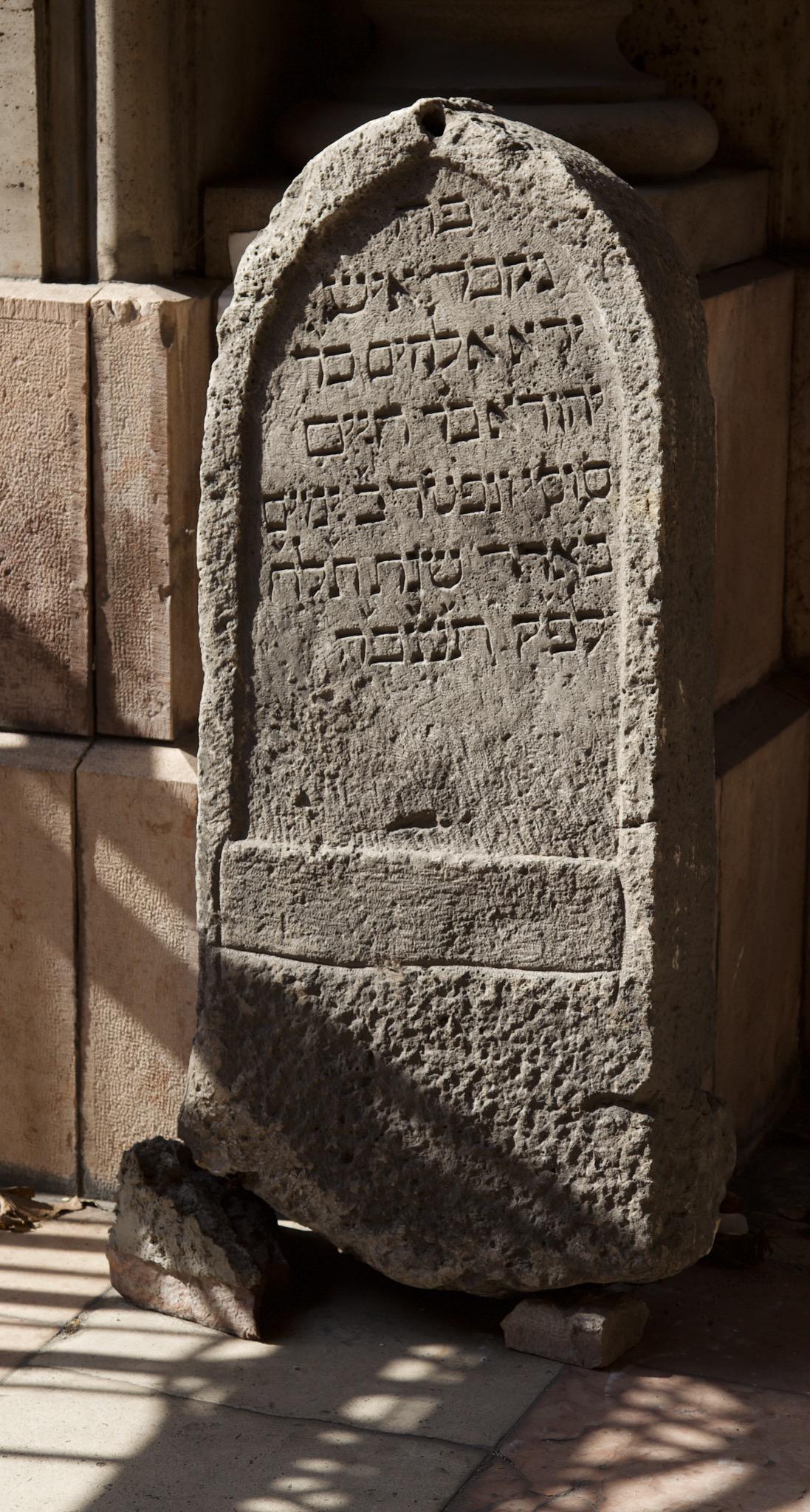

A lone gravestone, sentinel to a memory, leans against a wall on the grounds of the Dohány Street Synagogue in Budapest.

For more information about the Dohány Street Synagogue and related topics, click over to these secure websites:

budapest.org/en/great-synagogue

wikipedia.org/Arrow_Cross_Party

wikipedia.org/History_of_the_Jews_in_Hungary

dw.com/rising-anti-semitism-in-hungary-worries-jewish-groups