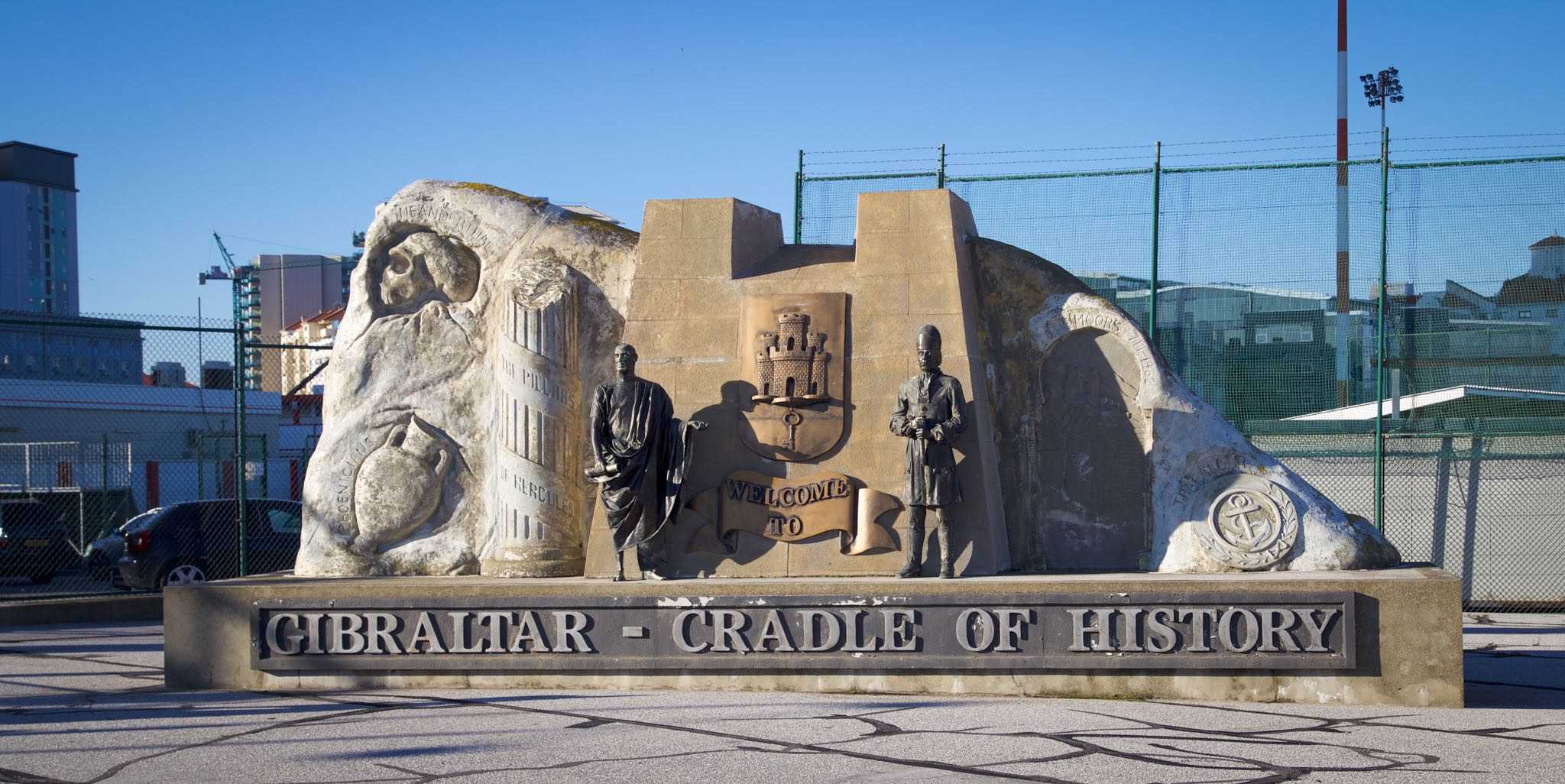

This monument as you enter Gibraltar from Spain encapsulotes the main elements of Gibraltar’s history. It is the first place Neanderthal remains were discovered, one of the Twelve Labors of Hercules, as part of the Western Roman Empire, the landing spot and an important locale of the Moors on the Iberian Peninsula, where countless battles were waged and won, and the north end of the Pillars of Hercules.

Gibraltar International Airport was completed by the British Empire in 1938 and built without consulting Spain, which was in the midst of a Civil War. The airport served as an important asset to the Allies during World War II. The east-west landing strip also accommodates foot, car, and truck traffic, which is halted when planes land and take off.

At only 2.6 square miles, to say Gibraltar is small is an understatement. The football pitch, just south of the airport runway, has opposing players readying for play and shows just how little space there is.

Gibraltar, a tiny, wind-swept crag may rank as the third-smallest territory on Earth, but it enjoys an outsized role in history and world affairs. It was a home for Neanderthals and early Homo Sapiens, was featured prominently in Greek mythology, was a battleground for a host of civilizations and religions, is the only European home for Barbary macaques, and served as inspiration for an iconic American advertisement that was in reality fiction ginned up as fact.

With just 33,700 residents, Gibraltar ranks as the 219th densest population center in the world, with 8,726 people per square mile. Early morning, before the square fills with people is a quiet time in the city.

Men gather at tables in the morning for a drink, a cup of coffee, and a quick chat before starting their day.

Located in the southern region of the Iberian Peninsula the area was a desirable spot for hominids, owing to a large number of limestone caves, proximity to the sea, and a generally warmer locale. The species known as Neanderthal was named after the hominid remains discovered in the Neander Valley in Germany in 1856. But the first of that species was discovered a full eight years earlier in 1848 at Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar, a sea-level cave at its southern end. The Neanderthal known as Gibraltar I was an adult female estimated to be between 60,000 to 120,000 years old. Gibraltar II was the second Neanderthal skull found in the early 1900s and was a child estimated to be between 30,000 to 50,000 years old. Gibraltar was one of the last locations where Neanderthals lived in Europe. Archeological evidence exists that early Homo Sapiens also resided in the area, suggesting the species overlapped.

On the west side of the spit is a large, sheltered harbor that has always been an important asset for the territory. In the center is a fuel transfer station where tankers can more safely offload cargo.

A commanding height is an excellent location to set up military outposts, and Gibraltar those defending Gibraltar have always taken advantage of that. This cannon high in the hills was used to protect the harbor below.

The hills and cliffs of Gibraltar rise up sharply from the sea, and enemy ships might slip underneath the cannon fire and pummel British soldiers on the land above. But in 1872 a clever Lt. Koehler developed this downward firing cannon that could drive away ships that tried to hug the shore.

The castle and defensive position, left, was built by the Moors and is just one of many military fortifications found in strategic locations all around Gibraltar that has made it an strategic location for tens of thousands of years.

Greek mythology noted the importance of Gibraltar as the site of one of the Twelve Labors of Hercules. The Labors were set down in an epic poem written by Peisander around 600 B.C. The logline of the story is Hercules went temporarily insane and killed his wife and children. Once recovered, as atonement, he was to carry out 12 labors. If successful, Hercules would be granted immortality. The Tenth Labor, the Cattle of Geryon, is where Gibraltar comes in. Hercules was to steal cattle from Geryon, a fearsome four-winged, three-bodied giant who lived in the westernmost region of the Mediterranean. To make a long story short, Hercules stole the cattle (prized for their coats stained red by the setting sun), slew Geryon, and smashed apart the mountain that stood in his way. The result is the Strait of Gibraltar and “The Pillars of Hercules.” The northern pillar is known as the Rock of Gibraltar, but then was called Calpe Mons. The southern pillar Abila Mons, is thought to be either Monte Hacho in Spanish-controlled Ceuta, or Jebel Musa in Morocco. The distance between the two pillars is 14 miles.

The plaque commemorates Gibraltar’s link to the ancient and Old World. The Gibraltar peak that rises 1,296 feet into the air is the north end of the Pillars of Hercules, the 10th of the Twelve Labors of Hercules of Greek mythology. Africa, 14 miles in the distance, can be see on the left.

The “public house” or more commonly, “pub” is the gathering place in many British locales and this one will be crowded once the day’s work is done. Neighbors and friends will enjoy a pint or two of beer and catch up with each other.

The territory called Gibraltar was named after a Berber from North Africa, Tāriq ibn Ziyād. Tāriq was a Berber commander who hailed from North Africa. Sometime in the early 700’s A.D. Tāriq was appointed governor of a region of North Africa, and the man who appointed him, Musa ibn Nusayr, sent his daughter to be educated in the court of Julian, Count of Ceuta (also in North Africa). But Roderic, a Visigoth king who was visiting Julian, raped Nusayr’s daughter. Enraged, Tāriq was dispatched from North Africa to the Iberian Peninsula to avenge Nusayr’s honor. Tāriq’s army of 7,000 horsemen landed in Gibraltar at the foot the mountain which was later named in his honor – Djabal Tarik – Tāriq’s Mountain (the cavalry was later supplemented with 5,000 soldiers). Tāriq was an exceptional battle commander and ended up capturing much of the Iberian Peninsula. It was not until 1492 that the Moors were driven from Spain.

This church in Gibraltar evokes a sense of serene refinement flanked by pennants and flags.

Though old and frayed, these flags are proudly and prominently displayed on the high walls of the church.

Once Tāriq came onto the scene, control and ownership of Gibraltar went back and forth for nearly 1,000 years – Muslims fought Christians, kings fought each other, and political greed was sprinkled in as an acrid spice. Spain prized Gibraltar as a critical outpost, and to guard the entrance of the Mediterranean. A formidable peak (running north south through the center of the land) reaches a height of 1,396 feet, there is a safe harbor on the western side, the location offers protection of Spain’s southern flank. But thanks to the fickle whims of fate and politics, Great Britain, with no likely claim to Gibraltar, gained a valuable prize.

Gibraltar is certainly small, but her location has made it a highly prized possession for any nation with the wherewithal to keep it. Once the British gained possession in 1715 thanks to the Treaty of Utrecht, they never let go. Chances are, it will forever remain in Britain’s grasp.

Great Britain’s windfall was all due to the War of the Spanish Succession (July 1701 – March 1714). The stage and players were assembled when King Charles II died in November 1700. He was a terrible choice as a king of Spain. Crowned when he was just four years old, he suffered from ill health and depression all his life (possibly due to inbreeding). Despite having married twice, Charles II was childless. To make matters worse he was not Spanish, but from the Hapsburg Empire. He died just a few days shy of his 39th birthday. To other European monarchs the greater concern was not who succeeded Charles as king, but who could control of the territories of Spain. At stake was the balance of power in Europe, and that greed sparked the War of the Spanish Succession.

During World War II, Gibraltar was an all-important military asset for the Allies. The Allied commanders and soldiers controlled the Strait of Gibraltar, and thus the Mediterranean Sea and access to the Atlantic Ocean.

France was a key player and had much to gain. To be fair, Charles II had bequeathed Spanish lands to his grandnephew Phillip of France, but only the French were interested in that salient fact. To thwart French ambitions an alliance of Great Britain, the Dutch Republic, the Vatican, and Austria rallied against the French. Fighting went on for nearly 14 years, and at the end, the Treaty of Utrecht was signed (it was negotiated and finalized from April 1713 to April 1715). As part of the treaty (and for a number of complicated reasons), Gibraltar was awarded to Great Britain; considered by many to have been the main beneficiary of the War of the Spanish Succession. But Gibraltar’s importance in world affairs was far from over.

Don’t worry, the four men on the left are not ignoring the two men on the right. The gentlemen laying on the cots are mannequins, part of a field hospital display.

In a small cemetery this grave site memorializes Lieutenants Thomas Worth and John Buckland who were killed by the same bullet on November 23, 1810 while commanding their Howitzer boat against the enemy in the Bay of Cadiz.

One group of residents enjoying a good life on Gibraltar could care less about the outcome of the War of the Spanish Succession. Barbary macaques may have been living comfortably in the area for as long as 5.5 million years. However, many believe they were brought over from Africa when Tāriq invaded the Iberian Peninsula in the 700s. To be more accurate, they are monkeys that originated from the Atlas and Riff mountains of Morocco. They are Gibraltar’s top tourist draw and the small population lives an easy and protected life. About 300 macaques live in five troops on the upper reaches of Gibraltar (though they will occasionally venture into the town). From 1915 through 1991 they were cared for by the British army (a task since taken over by the territorial government). The population is kept in check through birth control, the primates are well fed, and they are given identification tattoos and microchips to track the population. Births of offspring are announced in the local paper, and the young are often given the names of prominent military figures and important people. And while they are generally accustomed to people, they are still wild and can bite if annoyed or frightened. Feeding them is a strict violation and can result in a fine of up to $5,000 (£4,000). It is thought that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill once said that as long as Barbary macaques remained on Gibraltar, the territory would remain a British possession.

The Barbary macaques hold a special place on Gibraltar. They are well cared for, they are given healthy diets and they are the top tourist draw on Gibraltar.

While the macaques are accustomed to people and tourists, they can bite if they become frightened or annoyed.

When you have a monkey on your back, it’s best to just grin and bear it, as this woman appears to be doing.

An adult macaque gazes out to the harbor and the waters beyond, while a youngster grooms the adult, a behavior that increases bonds among the primates.

Grooming is a social behavior and also one that establishes hierarchy. This large adult enjoys the attention of several members of the troop.

The population of Barbary macaques is carefully monitored through microchips and tattoos, and breeding is controlled with birth control to avoid overpopulation.

During World War II Gibraltar was a vital asset for the Allies. (Remember, Portugal and Spain were technically neutral in the war.) Gibraltar’s commanding heights enabled the British to control who had access into and out of the Mediterranean Sea. That meant Allied sea traffic could be routed more directly through the Suez Canal, rather than all the way around Africa. The protected harbor on the west side of Gibraltar was a key refitting and refueling station that served Allied ships in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Inside the upper limestone reaches miles and miles of tunnels were excavated in order to house troops, command centers, supplies, and materiel. And the airstrip that bisects the territory at the northern end was used by Allied bombers and planes. In short, Gibraltar in Allied hands helped bring about a quicker conclusion to World War II.

The Grand Casement Gates are located on the northwest side of Gibraltar; and construction by the British began in the 1770s and was completed in the early 1800s. They are in the same vicinity of gates that had first been built by the Moors, so their strategic location and the protective walls that ran out from either side were already apparent.

This is 6 Convent Place, often referred to as “Number 6.” It serves as Her Majesty’s Government Headquarters, and the offices of the Chief Minister.

A changing of the guard at The Convent, which is the official residence of the Governor of Gibraltar. It was originally a convent for Franciscan friars in 1531, and has been the governor’s residence since 1728.

A sentry walks his post at The Convent, smartly dressed, stamping his spit-polished boot with authority.

Like honor guards the world over, this soldier takes his responsibility most seriously. His is a practiced, precise routine of march, turn and pivot, and then march back across the portico of Number 6. None shall pass who is not permitted.

Even though Gibraltar is only 2.6 square miles in total area, it has always had a prickly relationship with Spain. This began with the Treaty of Utrecht. Though she signed the treaty, Spain voiced objections to British possession of Gibraltar. There are still ongoing disputes as to exactly how much territory might have been awarded to Great Britain (Spain claims the British have control over just the old fortress area of the city, and has encroached into a neutral zone, while Great Britain claims a larger area). The airstrip was unilaterally built on neutral ground by the British in 1938 while Spain was busy fighting a civil war eventually won by General Francisco Franco. In the British referendum of 2016 to decide if Great Britain would exit the European Union (“Brexit”) more than 95 percent of Gibraltar residents who voted (83 percent) wanted to remain in the EU. Like the nettlesome Treaty of Utrecht, Gibraltar’s status with Great Britain, a relationship to Spain, and how it might or might not fit into a newly-configured EU is still open to debate.

The Europa Point Lighthouse, right, has been warning sailors of dangerous rocks since it first went into service in August of 1841. The former keeper’s quarters are to the left and the Rock of Gibraltar looms in the background, left.

About 1,000 Muslims are on Gibraltar and on August 8, 1997 the King Fahad bin Abdulaziz mosque was opened. It is the largest mosque outside of a non-Islamic country.

Even though Gibraltar is part of Europe and a territory of Great Britain, the iconic image of her dramatic, craggy peak was co-opted by an American insurance company as far back as 1896. Prudential Friendly Society (better known as Prudential Insurance), retained the services of the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency and devised with the slogan, “The Prudential has the strength of Gibraltar.” Despite the fact “The Rock” was riddled with a honeycomb of tunnels, it was a winning campaign. Using an enduring line drawing of the craggy peak, in later years the iconic phrase was added, “Own a piece of the rock.”

Despite its location at the southern end of Spain, Gibraltar has the look and feel of many communities one might find in Great Britain. Pubs with colorful names, like this one, are found in a number of spots in the territory.

To the world it is known as Gibraltar. To the locals who live there, she is referred to more casually as “Gib” (jib). But throughout history this small rocky spit of land has played a major role in the history of the world. Her reputation is secure, and she will always be, “Solid as the Rock of Gibraltar.”

Queen Elizabeth II is a popular monarch on Gibraltar, and when the vote for “Brexit” was taken, the territory’s residents voted overwhelmingly to “remain,” bucking the result back in Great Britain.

For more information about Gibraltar and its history, click over to these secure websites:

wikipedia.org/Rock_of_Gibraltar

thesun.co.uk/gibraltar-spain-brexit-overseas-territory-veto-rock/

wikipedia.org/Barbary_macaques_in_Gibraltar

wikipedia.org/Strait_of_Gibraltar

nhm.ac.uk/discover/2019/july/a-new-look-at-the-gibraltar-neanderthals.html