Mostar Bridge has been in use for more than 350 years, serving the culturally-diverse inhabitants along the Neretva River. It was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005 due to this aesthetic and cultural significance .

At its most basic, a bridge connects one side to the other and allows people to more easily make their way to and fro. A bridge can be an expression of beauty and design that identifies a thing with a place. When you see the Brooklyn Bridge you think of New York City, the Golden Gate and you know it’s San Francisco; Venice’s iconic Rialto Bridge, London’s Tower Bridge, the Chain Bridge in Budapest, and so many bridges around the world identify the cities they serve. Modern bridges are marvels of design that boggle the mind. In Mostar, what is now Bosnia y Herzegovina, the Stari Most bridge spans a spot along the Neretva River, and though a relatively small stone structure designed more than 600 years ago, it is an iconic symbol that identifies the city.

Mostar is located in the south-central area of what is now the nation of Bosnia y Herzegovina. Here, along this tributary that flows into the Neretva River just below the Mostar Bridge, cafes and restaurants are perched over the water providing an excellent view. The Prenj Mountains provide protection and the watershed feeds the Neretva River.

A number of distinctions makes the City of Mostar special. The area has been occupied by humans since prehistory (at least 3,000 years ago); the river has served as an artery of commerce, a Roman Empire-era settlement once thrived there, and the location has been as a gathering point of cultures. Over the centuries several Western religions erected churches, temples, and mosques there. And Mostar is located in a region of far southwestern Europe that has been the scene of tragic wars and bloodshed that go back more than 100 years. The Mostar bridge is recognizable to people around the world.

An early morning photograph at the Mausoleum of Osman Đikić, a Bosnian poet who died in 1912 at the young age of 33. He is regarded as an important poet and dramatist whose work tended toward the didactic.

In comparison with other famous bridges, Mostar’s is quite small. Its length is just over 95 feet, a height above water of nearly 79 feet, and a width of just over 13 feet. (By comparison, the Golden Gate Bridge is almost 9,000 feet in length, approximately 200 feet above the water, and has a width of about 90 feet.) But, getting a bridge to span the banks of the Neretva River in the 14th Century was difficult; previous rope and suspension designs failed, which impeded Mostar’s growth. Around the mid 1400s, the Ottomans ruled the area (the first recorded name of the city was around 1474 as “mostari” or “bridge keepers”). By the 1550s Ottoman ruler Suleiman the Magnificent ordered the design and construction of a permanent structure. Architect and civil engineer Mimar Hayruddin was tasked with the job. But the sultan’s exasperation with previous failures prompted him to add an incentive clause: if the bridge failed, Hayruddin would be put to death.

The Mostar Bridge is limited to foot traffic and the ridge stones make it clear that in rainy or inclement weather the surface can be slippery.

Like so many centuries-old cities, Mostar is a maze of small streets that are still in use today.

The Neretva River that flows underneath the bridge is a water highway that served as a vital economic element to Mostar’s development. Today commerce moves by big-rig trucks along modern highways that link up with the nations of Europe.

Hayruddin labored on the design and construction for nine years. He chose a graceful arch, which is easy on the eye and self-supports the load, eliminating the need for a pillar in the river that would bottleneck boat traffic up and down the waterway. But the specter of previous failures gave Hayruddin doubts. So he hedged his bets. Hayruddin began digging his own grave. If the bridge failed, he would take comfort that he chose his own final resting place.

Architect and engineer Mimar Hayruddin was assigned the task of designing a permanent bridge across the Neretva River. The failure of previous efforts prompted the sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to motivate Hayruddin with an incentive — if the bridge failed he would be put to death.

Part of what makes Mostar special is the blend of cultures that are deeply rooted in the city. A variety of high quality handicrafts by talented craftsmen can be found in shops in the city’s center.

Hand-punched tin items is a craft Mostar is known for. This man carefully works on a piece that will be later sold to a happy buyer.

Just outside of the city center is a weekend open-air market where vendors sell fresh vegetables, fruits, wares, and in this case, home crafted spirits called rakia. These fruit-based liqueurs are made from a variety of fruits and they pack quite a punch. Makers sometimes joke, “The fruit’s no good for eating but it makes good rakia.”

But lo and behold, when the final scaffolding was removed and the bridge opened to traffic in 1566, it not only held, but endured for 427 years. Hayruddin would go on to live another 22 years and he died in 1588. The structure’s design is praised as an outstanding example of Ottoman bridgework. And thanks to the bridge, the city of Mostar prospered and became an important link of commerce, culture, and religion. Thanks to Hayruddin, it is highly likely the bridge would have remained in place to this day. But in 1993 the dark hearts of hatred and war plagued that region of the Balkans and erupted into conflict known as the Yugoslav Wars.

Like so many parts of the former Yugoslavia, Bosnia y Herzegovina suffered terribly during the Yugoslav Wars. The damage to this building shows the scars of war. Lacking of funding and investment makes rebuilding slow.

A work crew puts a new roof on a house in Mostar. The “shingles” are large flat stones that are set in place and secured with mortar.

A work crew takes a mid-morning break on a roofing job along a commercial street in Mostar. The city continues to be rebuilt with houses, shops, restaurants, cafes, and hotels.

The death of Josip Broz Tito in May of 1980 marked the beginning of the end of Yugoslavia, a complicated region of disparate cultures and religions. Tito had skillfully succeeded in holding together a “non-aligned” nation. He deftly avoided becoming a lackey of the USSR, headquartered in Moscow, or the under-appreciated vassal of Western-capitalist nations (with the United States as the leading influence). After Tito’s death the ghosts of ethnic and nationalist discord festered, resulting in a series of bloody wars; atrocities, ethnic cleansing, war crimes, and ruin were suffered by the region’s inhabitants. Today, the former Yugoslavia is now six independent countries, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Bosnia y Herzegovina, along with two autonomous regions, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

The fighting may have stopped, but remembering the residents of Mostar, and the visitors who come to this beautiful city, are reminded of the sacrifice that was made, based on the graphic on the upper right corner.

These shops, approaching the Mostar Bridge are in an ideal location to attract tourists and shoppers.

A number of cultures have become part of Mostar’s history, and shoppers can find a number of bright, colorful items to take home.

But back in November 1993 Bosnian Croats were locked in a fierce battle with Bosnian Muslims and fighting was underway in and around Mostar. Bosnian Croat gunners trained their fire on the bridge and destroyed it. What had stood for more than four centuries was now rubble and would stay that way for about a decade. But within months after its destruction UNESCO launched a campaign to restore the structure. Rebuilding began in June 2001 and was completed in July 2004. In 2005 the bridge was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The original architect and engineer who built the Mostar Bridge, Mimar Hayruddin, succeeded on several levels. First, the bridge has stood for more than 350 years (even accounting for the years it was destroyed then rebuilt 2001 — 2004), second it is highly functional by employing an arch design, thus keeping a support pillar out of the river, third it is an eye-pleasing design, and finally, it has served as proof to the people of Mostar and those around the world that a bridge can connect more than just one side to the other.

The restored bridge continues its role as an anchor to serve the people and businesses of Mostar. And thanks to an ancient tradition that has been reworked for modern times, it is possible to jump off the bridge at the center and plunge into the river below. Legend has it that in 1664 a 16-year-old boy leapt from the bridge as a rite of passage and also to ensure his life would not be a failure. The daring of the boy’s exploit continued to be romanticized and in 1968 a bridge diving festival began and takes place toward the end of July each year. But over the years taking the plunge has resulted in at least four deaths and many injuries.

The Mostar Bridge can be seen from a number of vantage points around the city, and in this moment the morning light cuts across the center of the bridge, preparing to light the entire city at the start of a new day.

There are a number of spots in and around Mostar to view the bridge and photograph it. Appreciating the beauty of Hayruddin’s creation, and having some understanding of the area, gives one hope that history and the importance of linking people together shows the Mostar Bridge is more than its basic function of spanning a river. It can also be a bridge to that which divides us.

Mostar’s location along the Neretva River, and its tributary affords a reliable flow of water.

A small arched foot bridge along a tributary of the Neretva River links one part of Mostar with another, a convenience to residents, and a benefit to visitors strolling around and taking in the sights of the city.

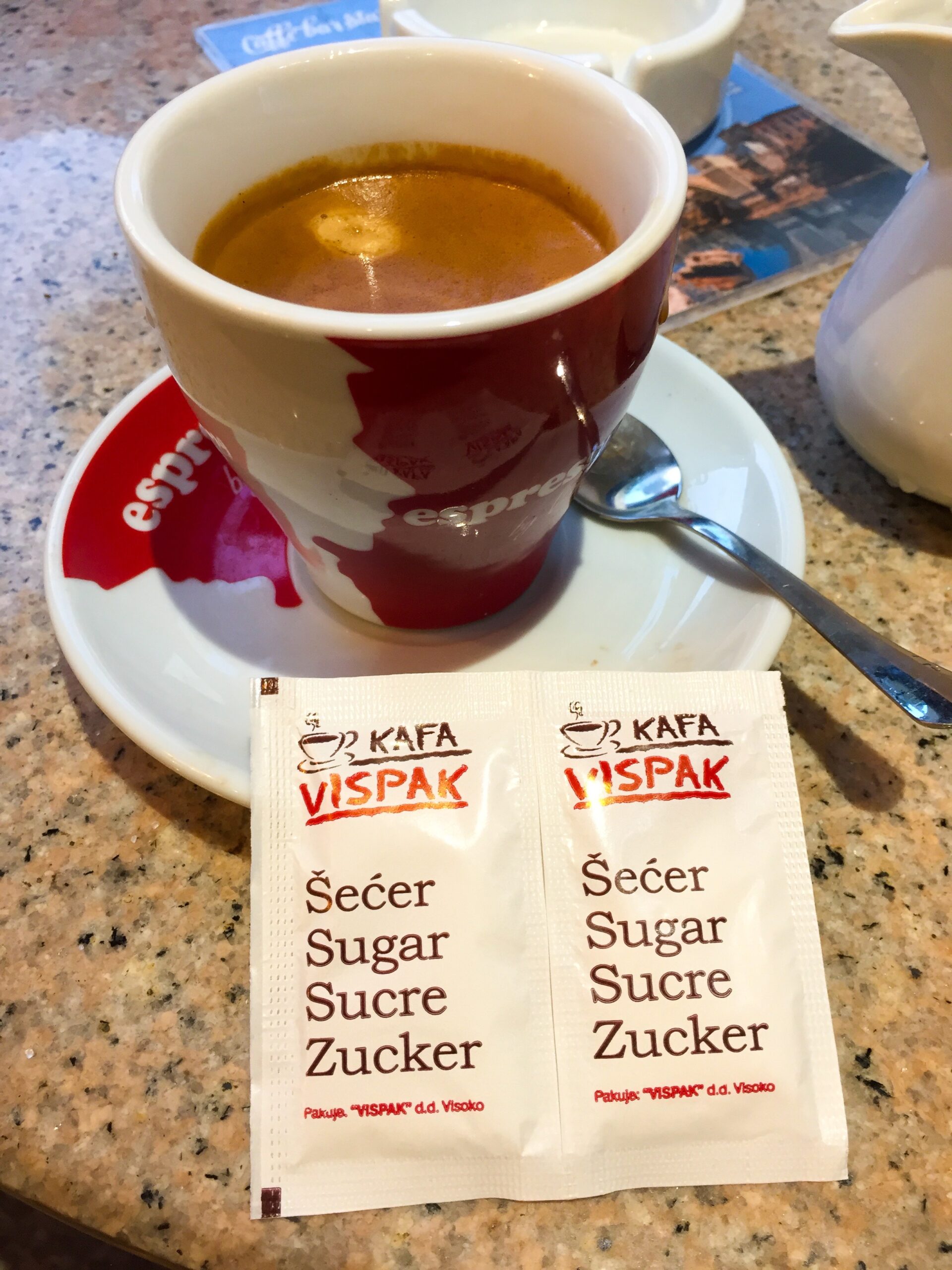

Mostar serves a Turkish-style coffee which uses very finely ground beans that are unfiltered. To best enjoy your cup of this strong drink, do not slosh the liquid to allow the grounds to settle, and don’t drain the cup or you will drink the bitter grounds. Sugar and a dollop of milk help soften the bitterness for first drinkers of this brew.

Beer, like this local variety, is a quality product throughout the Balkans and either with a meal, or as a refresher following a stroll about the city. A glass or two is a good way to relax in Mostar.

For more information about Mostar and its iconic bridge, click over to the secure websites below: