Frida Kahlo experienced great pain. This self portrait shows the complex and painful nature of her life.

Frida Kahlo created art at a price paid dearly. “Tortured artist” understates the pain she endured much of her life, pain both physical and emotional. But it was in the cauldron of conflict where she produced some of her greatest work. And while she lived in many places in Mexico City and around the world, the idyllic home known as the Blue House – Casa Azul – was a touchstone throughout her life.

Casa Azul — the Blue House — was the Kahlo family home where Frida lived, returned to often and died.

Visitors from all over the world to see Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul, in the Coyocan neighborhood, now part of Mexico City.

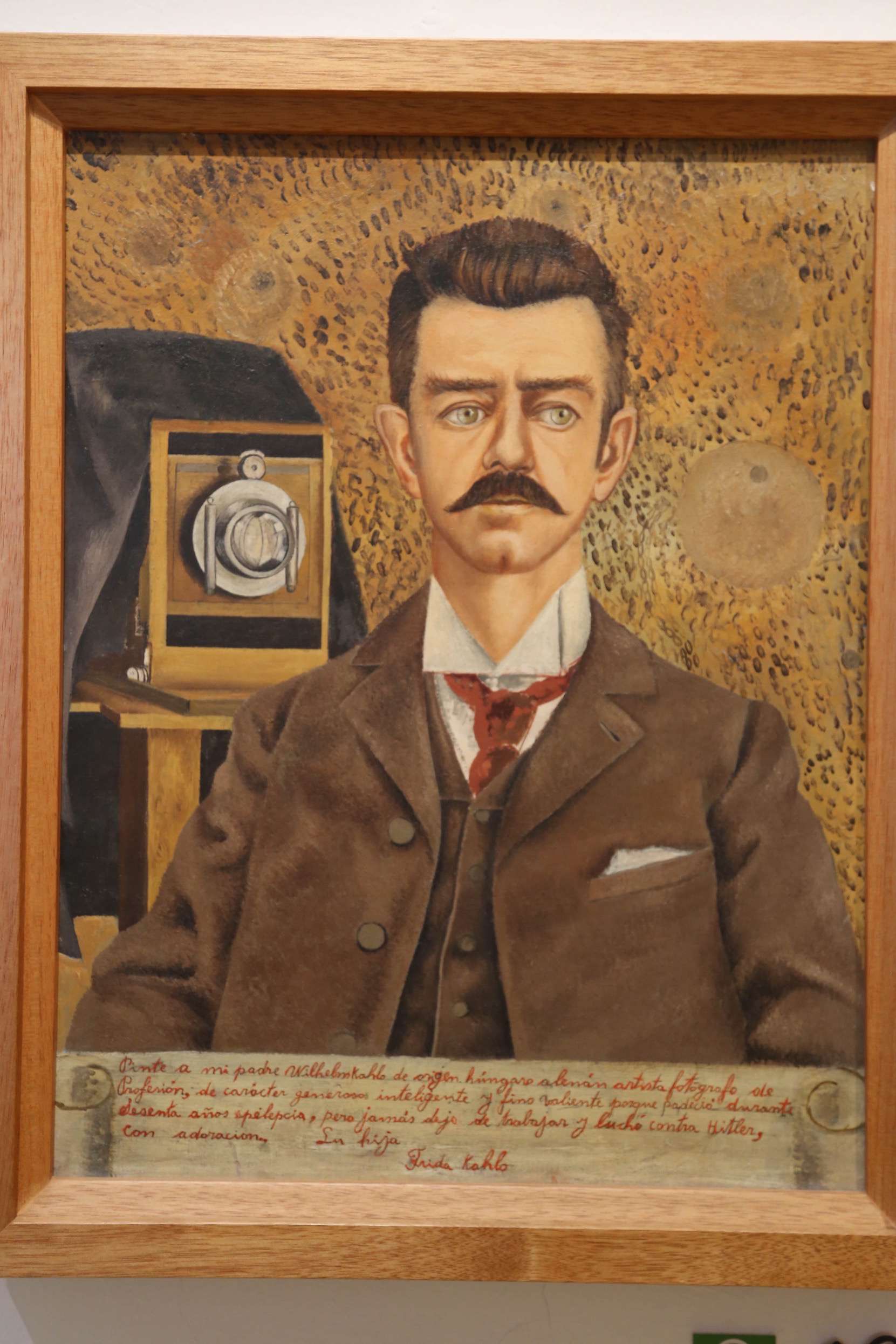

To better understand Frida Kahlo, it helps to know something of her father, Guillermo Kahlo. The two shared a number of traits. Both had complicated lives, suffered serious injuries in their youth, were introspective and moody, and both had a keen artistic eye and aesthetic, among other things.

Guillermo Kahlo, Frida’s father, was a talented and successful photographer in Mexico City. Frida painted this portrait of him. She was the only one of his six children he was close to.

Born Wilhem Kahlo, the Hungarian-German Jewish immigrant arrived in Mexico in 1891 and changed his first name to Guillermo (Wikipedia reports he was a German Lutheran, but information at Casa Azul as well as university research says he was Hungarian-German and Jewish). Guillermo pursued several lines of work before finding success as a photographer in Mexico City. He had previously sustained a serious injury that left him plagued with episodes of epilepsy, and the injury may have contributed to his melancholy and moodiness.

This family portrait by Frida Kahlo shows the generations of her family and the people important in her life.

Matilde Calderon y Gonzalez, Frida’s mother, was Guillermo’s second wife. His first wife died while giving birth to their second child. The subsequent marriage to Maltide was one of convenience more than love. Nonetheless Matilde and Guillermo had four children, and Frida was their third child, born in 1907 (though she would cite her birth year as 1910 to coincide with the Mexican Revolution). Guillermo’s first two children were raised alongside Frida and her siblings.

Visitors pause on a outdoor patio as others stroll the grounds at Casa Azul.

Guillermo did not form strong emotional bonds with his children but Frida was the exception. That may be because when Frida was six years old, she came down with polio (her left leg ended up being smaller and weaker). Guillermo may have recognized the pain polio inflicted on her along with his own pain from his earlier head injury. Frida and her mother did not have a loving relationship and in fact were often at odds with each other.

While Guillermo Kahlo photographed Frida when she was a young girl, this portrait was shot by someone else when she was an adult. Frida knew how to strike a telling pose for a photo.

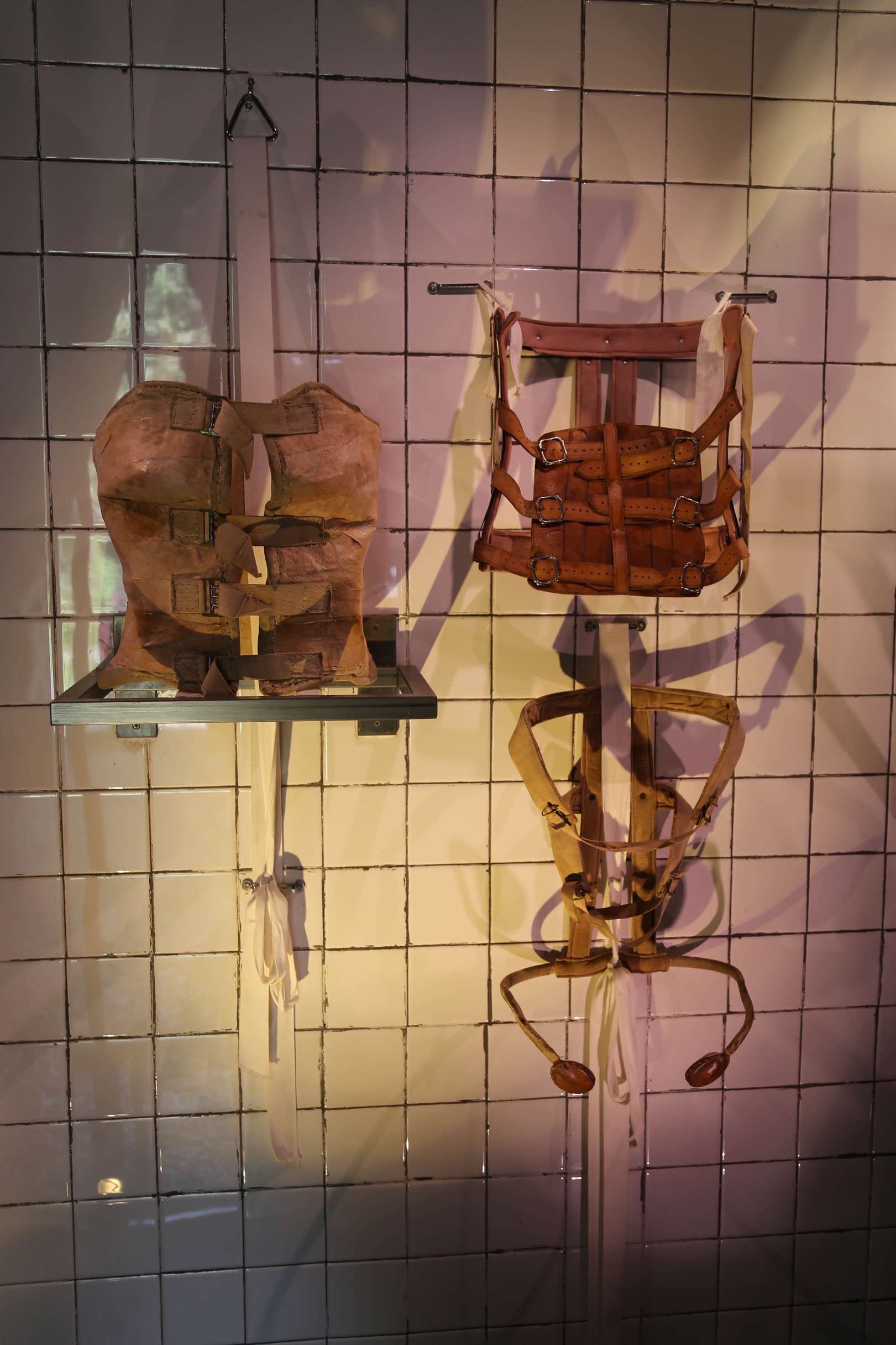

Frida Kahlo adopted a style of dress that was as much cultural as it was disguise of the harnesses she had to wear.

Beneath the colorful and flowing dresses Frida Kahlo wore was a cumbersome set of harnesses and braces.

The success Guillermo enjoyed as a photographer may well have served as a gateway to Frida’s emergence as an artist. Originally, Frida considered a career in medicine and was a promising student. She also spent time with her father and as an occasional photographic subject for Guillermo.

This gallery, when you first enter Casa Azul, contains many of Frida Kalho’s paintings and captures her distinctive style.

But when she was 18, Frida was very seriously injured in a trolley accident; the effects would have a profound effect on her and crushed any possibility of a medical career. Her back was broken, along with a collarbone, ribs and a shattered pelvis. Her right leg was broken in 11 places, her right foot was dislocated and crushed and a metal bar pierced her uterus. She underwent approximately 30 surgeries to repair the damage. Later in life she tried to have children but miscarried three times (one of which was in 1932 in Detroit, Michigan). She endured bouts of pain throughout the rest of her life.

Frida Kahlo painted while lying in this bed and her mother had a mirror installed on the ceiling so Frida could work on self-portraits. Her death mask is draped in a shawl.

Those devastating injuries took nine months for her to make an initial recovery.

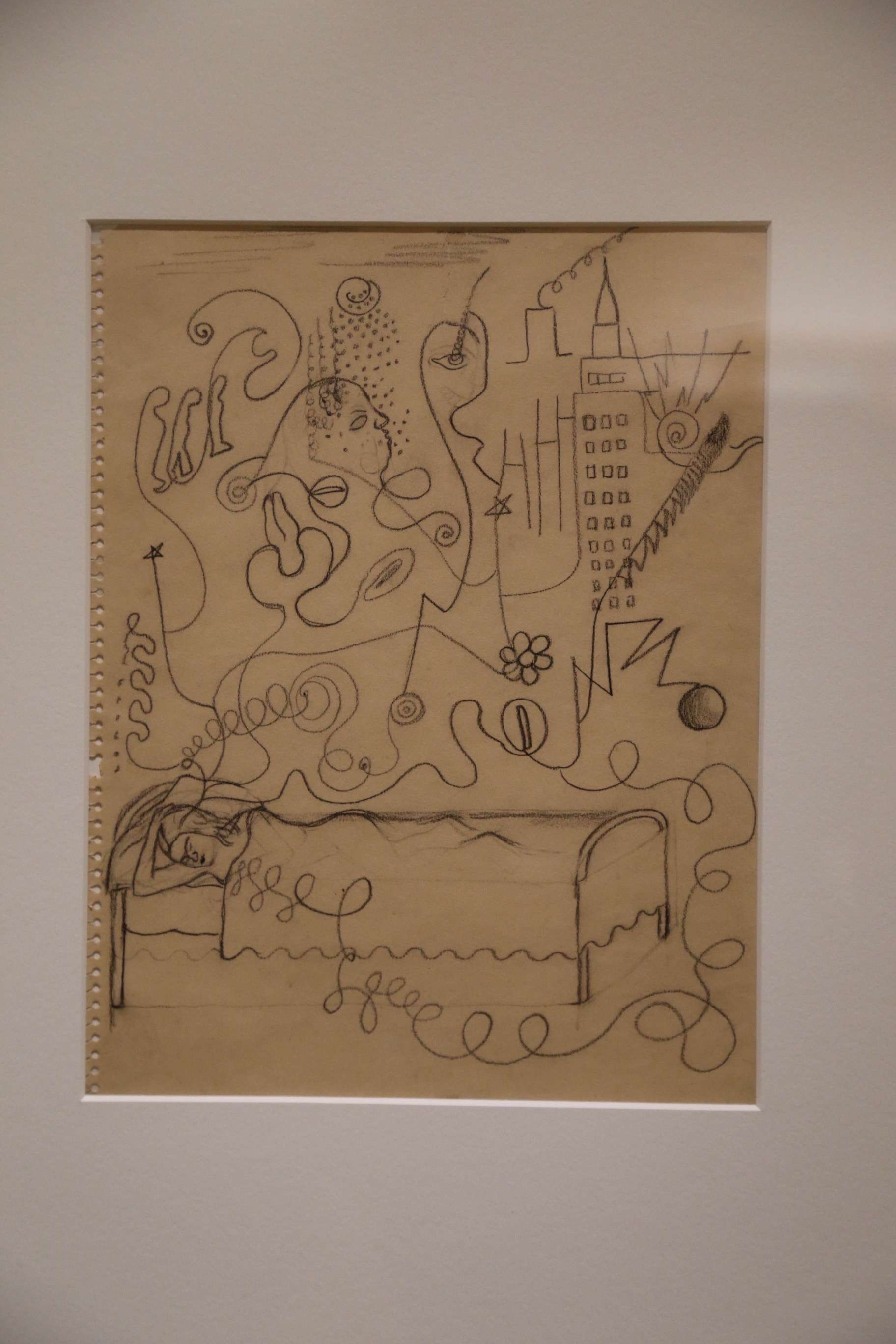

This tortured sketch shows many of the complex and painful elements in Frida Kahlo’s life. She began to paint while lying in bed, during her grueling recovery from the injuries she sustained at age 18.

Frida Kahlo traveled quite a bit in her life and she collected numerous momentos, like in this cabinet at Casa Azul and the photo of V.I. Lenin, top.

During that time she began to paint, mostly self-portraits. Many of the things she experienced during her life were made a part of her paintings. Of the 140 paintings she executed during her life, 55 are self-portraits. She famously said, “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best.” Many of her self-portraits reflected elements of pain, feelings about her infertility, showing herself nude, the indigenous and mixed-race nature of her heritage, and religious themes, both Christian and Jewish. “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality,” she said.

Frida Kahlo would tell people that she painted reality, not dreams, and painted what she saw.

Several years after her accident and while she was just beginning as a painter, she sought advice from Diego Rivera, universally acknowledged as one of Mexico’s great artists and muralists. Rivera recognized her talent, encouraged her efforts and offered his own insights into her work. They met in 1928 and as they became better acquainted, they both realized they were communists in their political views.

Frida Kahlo had to wear braces and appliances to help her stand straight. The one on the left is embellished with a hammer and sickle, keeping the symbol of communist ideology close to her heart.

They married in 1929, and Frida’s mother disapproved of the marriage. This should come as no surprise, because Rivera was married to his second wife when he began to woo Frida, and Rivera had children with his two other wives. Later, Frida might have been agreeing with her mother, because she is reported to have said, “I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down… The other accident is Diego.”

Pain was a constant in Frida Kahlo’s life after her terrible accident when she was 18 and these harnesses are examples of what she wore regularly.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera had a tempestuous relationship. Both were easily irritated. Both Frida and Rivera had affairs during their two marriages. (They divorced in in November 1939 but remarried in October 1940.) Frida was bisexual and had an affair with Josephine Baker, among others. Rivera did not appear to mind Frida’s affairs with women, but her affairs with men made him very jealous. For his own part, Rivera carried on an affair with Frida’s younger sister, which angered and deeply hurt Frida. The couple often slept in separate rooms.

A tile inlay, in a shallow pool outdoors at Casa Azul, is a reference to Diego Rivera, whose nickname was “Toad” in nod to his large eyes and lips.

Frida Kahlo’s studio, upstairs at Casa Azul. Paints, brushes and a mirror at the ready as she worked and created many of her self-portraits.

This ingenious easel was a gift from the Rockefellers who were fond of Frida, despite their frustration with Diego Rivera.

A working area of Frida Kahlo’s studio at Casa Azul, with a photo of Diego Rivera on the right.

Communist political beliefs would cause difficulties at least several times during their lives. In 1934 Rivera was embroiled in a scandal in New York when a mural he had been commissioned to paint at Rockefeller Center was revealed to feature communist elements – antithetical to the capitalist Rockefellers. Once Rivera’s work was understood, it was chiseled off the wall. Rivera later recreated the mural at Mexico City’s Bellas Artes.

This is the mural Diego Rivera painted for Rockefeller Center in New York City, before the Rockefeller’s discovered its communist elements and had it chiseled off the wall. Rivera later recreated the masterpiece at Bellas Artes in Mexico City.

Later in the 1930s, Leon Trotsky came to Mexico City and for a time he stayed with Rivera’s home and then later moved over to Frida Kahlo’s home, where the two had an affair. Diego and Frida later broke with Trotskyism and embraced Stalinism in 1939.

Frida Kahlo believed in communism and this photo on a wall at Casa Azul shows Kahlo with her friend, and lover, Leon Trostky, second from the left.

In 1938, Frida went on a solo trip to New York City where she began a 10-year affair with Hungarian photographer Nickolas Muray.

The overalls hanging on the wall and the hat to the right belonged to Diego Rivera.

But good health eluded Frida. Along with her recurring pain she would experience respiratory problems, and in July 1952 her right leg was amputated at the knee when gangrene developed.

Frida Kahlo lived much of her life in great physical pain. In 1954 her right leg was amputated at the knee when she developed gangrene. She used this prosthesis.

By 1954 she was near the end. Her physical ailments were exacerbated by panic attacks and Frida was consuming increasing amounts of morphine. Only 47 when she died on July 13th of that year, her official cause of death was listed as pulmonary embolism, though some suspect she overdosed on morphine to end her own life. She wrote in her diary shortly before her death, “I hope the exit is joyful, and I hope never to return.” There was no autopsy and she was cremated, in accordance with her wishes. A pre-Columbian urn containing her ashes rests at Casa Azul.

The grounds at Casa Azul are peaceful and inviting.

In 1958 Casa Azul was repurposed and named Museo Frida Kahlo. Today it is a very popular tourist destination.

The kitchen at Casa Azul. Though modern stoves and ovens were available, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera liked to cook in a more traditional manner.

Frida Kahlo’s life was one of tumult and pain. Through all she endured, this frail and diminutive woman created a legacy as one of the world’s foremost women artists. She is recognized throughout the world for her talent, vision and strength.

The dining area at Casa Azul shows the bright colors and traditional themes that are found throughout.

For more information about Frida Kahlo, visit these websites:

museofridakahlo.org.mx/casa-azul

wikipedia.org/wiki/Frida_Kahlo_Museum

wikipedia.org/wiki/Frida_Kahlo

biography.com/people/frida-kahlo

theartstory.org/artist-kahlo-frida